By Rebecca Sherman

Jolene Hardesty has faced challenges in her 20 years of public service—from her early days as a 911 sheriff’s office dispatcher to her current role as Missing Children’s Clearinghouse Analyst and Missing Persons Coordinator for the Michigan State Police.

And while she has helped rescue an estimated 600 children by providing analytical, resource, and training support to regional, state, federal, and Tribal law enforcement, she can now count another challenging assignment as a win: 15 months of service on the Not Invisible Act Commission.

For Hardesty, the experience was equal parts daunting, rewarding, and eye- opening. She worked with 35 others from across the nation to fulfill the Commission’s goals, as follows.

- Identify, report, and respond to cases of missing and murdered Indigenous people (MMIP) and human trafficking.

- Develop legislative and administrative changes to enlist federal programs, properties, and resources to help combat the crisis.

- Track and report data on MMIP and human trafficking cases.

- Consider issues related to the hiring and retention of law enforcement officers.

- Coordinate Tribal, state, and federal resources to combat MMIP and human trafficking on Indian lands.

- Increase information-sharing with Tribal governments on violent crimes investigations and criminal prosecutions on Indian lands.

The Commission held hearings across the nation, receiving heartbreaking yet critically important testimony from hundreds of victims, survivors, family members, family advocates, and members of law enforcement.

In the fall of 2023, Hardesty and her fellow Commissioners submitted their final report to U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland, the U.S. Department of the Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, and Congress.

With May designated as Missing and Murdered Indigenous Peoples (MMIP) Awareness Month (and May 5, National MMIP Day, also known as “Wear Red Day”) we talked with Hardesty about her work on the Not Invisible Act Commission—and what’s on the horizon.

Tell us a bit about your work on the Not Invisible Act Commission.

Each day was spent gearing up and prepping for meetings. I read a lot—federal statutes, statistical reports, and notes from other initiatives prior to the Not Invisible Act, such as Operation Lady Justice. Many weeks we met multiple times and brought in subject-matter experts to answer questions. I also gave in-person [congressional] testimony in D.C. as an expert on missing children, and traveled to Minnesota and Montana for public testimony. We were organized into subcommittees based on our experience. I was co-chair of Subcommittee Two, which focused on MMIP data. And on Subcommittee Four, we looked at coordinating resources, criminal jurisdiction, prosecution, and information sharing— for instance, understanding how the NCIC [National Crime Information Center] database is aggregated, and what shortfalls it presents.

![Information sidebar: Not Invisible Act: Key findings Jolene Hardesty shares thoughts from her Not Invisible Act Commission work. Resources are desperately needed. “We heard testimony from an Alaska Native woman whose sister was murdered in her home—and she lay dead on the floor for three days because no police came to investigate,” Hardesty says. “There are also villages in Alaska that don’t have a fire department; villages that take a State Trooper three days by airplane to reach; and villages where Tribes don’t have a police department—or if they do, officers are not staffed 24/7. These departments lack the funding, resources, people, or skill sets to have an appropriate response, much less an immediate one.” Jurisdiction can be a problematic puzzle. In Oklahoma, where nearly half the land is Tribal owned, “you have a checkerboard of different Tribes, and criminal jurisdiction isn’t clear,” she says. For instance, a crime that happens on the northwest quadrant of a street may be the responsibility of a different Tribe than one on the southwest quadrant. And if the crime is murder, another jurisdiction may need to be involved. “Keeping up with the matrix needed to determine who’s going to respond to a crime can be overwhelming,” she says. Justice is often meted out differently. “Tribal law enforcement and courts are limited in what they can do [and often include social-rehabilitation measures]. If a murder occurs on Indian land, the most jail time imposed [may be] nine years,” Hardesty says.](https://amberadvocate.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/16b-Key-Findings.png) How does the way data is collected present a problem?

How does the way data is collected present a problem?

In NCIC, there aren’t enough race categories—it’s either “Alaska Native” or “American Indian.” Beyond that, it’s also important to know if a person is a member of the Cherokee or Crow Nation, for instance, or maybe also affiliated with another Tribe. Grouping people into one category doesn’t serve justice when you are at the granular level of an investigation.

Why is the term “Indian” still used by government officials?

Growing up I was taught that term was offensive, but during my work for the Commission, I learned that when you’re speaking about Native American land, the legal term is “Indian Country.” Additionally, Alaskan Natives don’t like being called “Indian”—they live on Alaskan land. But if we explain why we need to use the term in certain circumstances, it goes a long way to show respect. I found that changed the entire conversation when talking with Native partners.

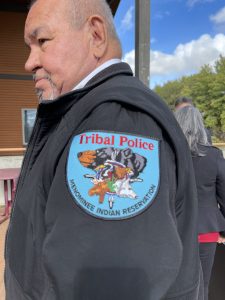

How have you built bridges of respect with your Native American partners?

By creating relationships. I reached out to our Mount Pleasant post in Michigan and the Saginaw Chippewa Tribe Police Chief and asked them to be experts on relationship matters. Michigan is home to 12 federally recognized Tribes and a few that are not. And in the state’s not-so-distant past, there were at least three state-funded Indian boarding schools, where Indigenous people were not allowed to speak their language, celebrate traditions, or practice their religion. Because of that, Native American law enforcement partners and citizens often associate non-Native [law enforcement/legal] personnel with trauma. It’s important to acknowledge that, to tell them you understand why they may not trust us. Relationships built on a foundation of mutual respect are critical. You’ve got to be able to have difficult conversations with one another honestly and openly, and still be able to respect each other. Accomplishing this is possible, but takes intentional work on both sides.

Tell us about the importance of cultural awareness and historical training.

Learning about the culture really helps. For example, when non-Native people get sick, they go to the doctor. But for Native peoples, it’s very different. [When going to] Indian Health Service care, a person is asked, “How much Indian are you, and what kind?” Some clinics only serve members of certain Tribes. All that matters before treatment. So that’s the kind of thing our Indian partners face on Indian land. Historical awareness is also important [to understand inherent conflicts between Tribes]. Many were warring Tribes for generations before [the U.S. government] put them on the same reservation and said, “Be happy.”

How have you approached the complexities involved in working with different Tribes?

Every Tribe needs its own voice to be heard, and this takes significant communication and collaboration. The best way to address our Tribal partners’ needs is to ask them. We should ask them not only “What do you need?” but also, “What can I help you with?”

As you reflect on your Commission work, what’s next for you?

My work on the Commission was some of the hardest I’ve done. It was frustrating at times, and I had a huge learning curve, but I feel like I’ve helped, and know I’ve made connections with some phenomenal people. And while I’m sad to see the Commission’s work come to an end, I look forward to the next goal: Implementing AMBER Alert in Indian Country. For many of us on the Commission, the focus will be to bring our Native American partners to the table as advisors, equals, and subject-matter experts. Together, we can really address their needs.

“As of today,

“As of today,

The Technology Toolkits—durable cases with high-tech equipment to help Tribes act quickly when a child goes missing—were provided for free to the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa; Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe; Lower Sioux Indian Community; Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe; Upper Sioux Community; and the White Earth Nation. Five other Minnesota Tribes also have received the Toolkits.

The Technology Toolkits—durable cases with high-tech equipment to help Tribes act quickly when a child goes missing—were provided for free to the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa; Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe; Lower Sioux Indian Community; Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe; Upper Sioux Community; and the White Earth Nation. Five other Minnesota Tribes also have received the Toolkits.

Toolkit

Toolkit

These Technology Toolkits are being provided to Tribal communities that currently administer their own AMBER Alert program, or that participate in (or are in the process of adopting or joining) a regional or state AMBER Alert plan.

These Technology Toolkits are being provided to Tribal communities that currently administer their own AMBER Alert program, or that participate in (or are in the process of adopting or joining) a regional or state AMBER Alert plan.

With the signing of a proclamation declaring May 5th as Missing and Murdered American Indians and Alaska Natives Awareness Day, President Trump has taken a step forward in our nation’s efforts to raise awareness and protect Native American and Alaskan Native communities.

With the signing of a proclamation declaring May 5th as Missing and Murdered American Indians and Alaska Natives Awareness Day, President Trump has taken a step forward in our nation’s efforts to raise awareness and protect Native American and Alaskan Native communities. The American Indian and Alaska Native people have endured generations of injustice. They experience domestic violence, homicide, sexual assault, and abuse far more frequently than other groups. These horrific acts, committed predominantly against women and girls, are egregious and unconscionable. During Missing and Murdered American Indians and Alaska Natives Awareness Day, we reaffirm our commitment to ending the disturbing violence against these Americans and to honoring those whose lives have been shattered and lost.

The American Indian and Alaska Native people have endured generations of injustice. They experience domestic violence, homicide, sexual assault, and abuse far more frequently than other groups. These horrific acts, committed predominantly against women and girls, are egregious and unconscionable. During Missing and Murdered American Indians and Alaska Natives Awareness Day, we reaffirm our commitment to ending the disturbing violence against these Americans and to honoring those whose lives have been shattered and lost.

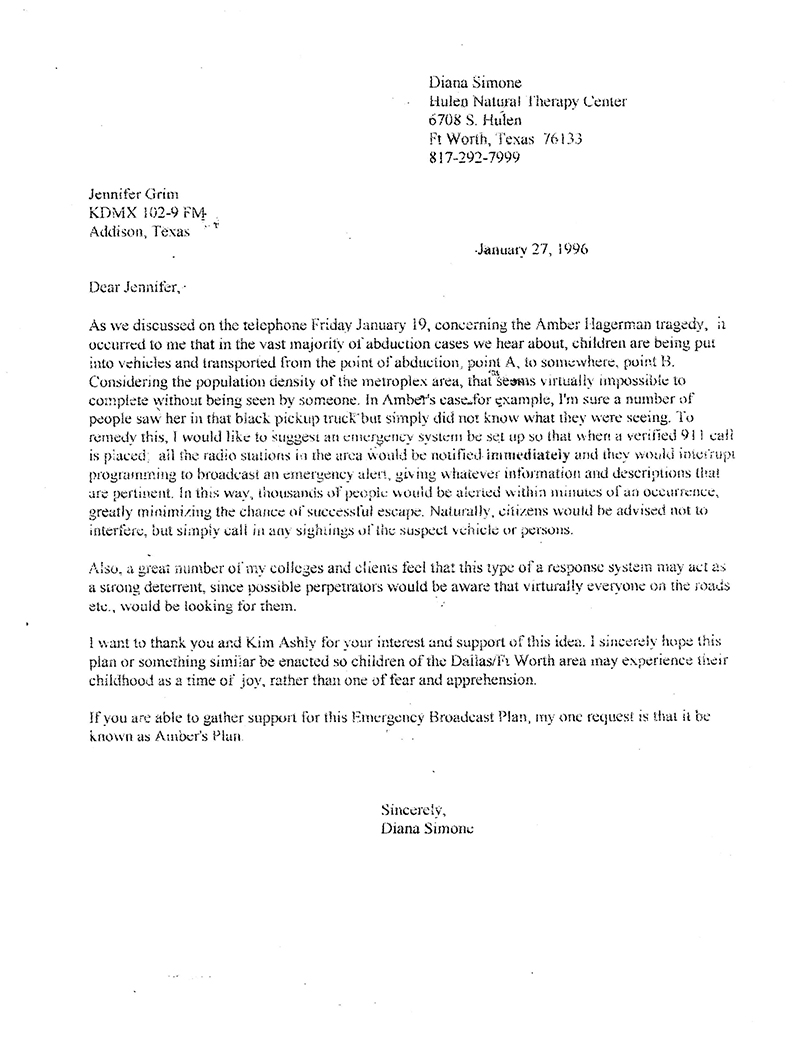

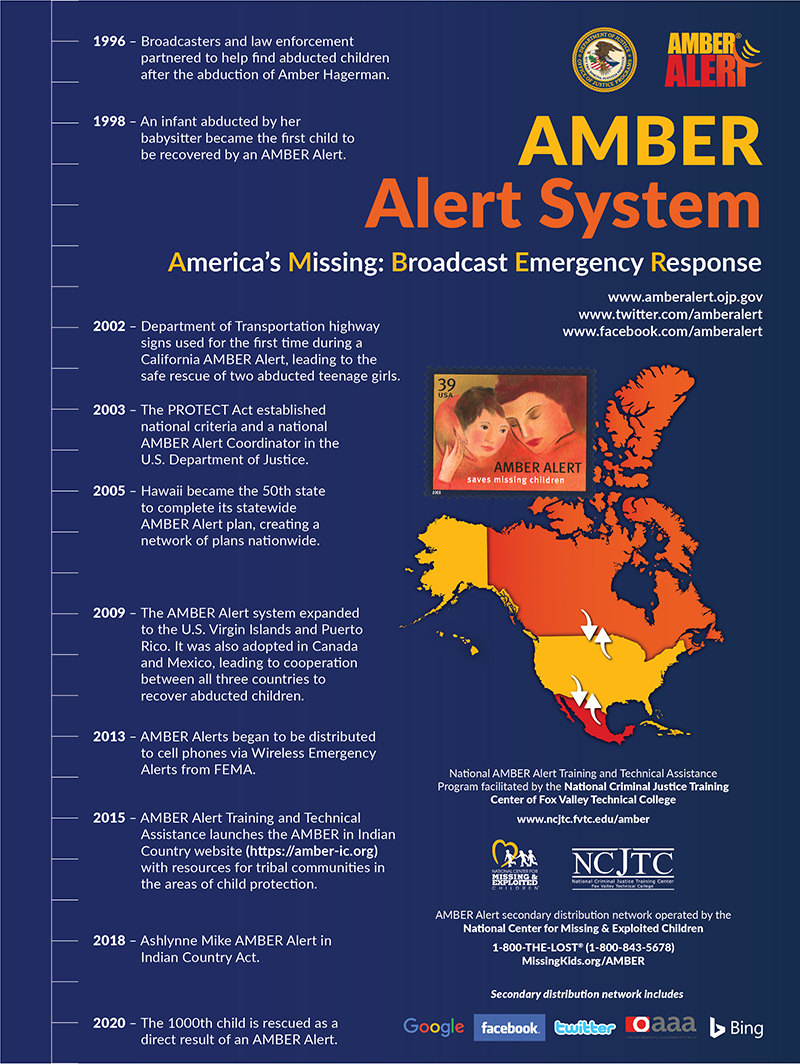

When a child is abducted, every second counts—and every decision matters. AMBER Alert is an early warning system that activates an urgent bulletin to galvanize community support and bring a missing child home. It is a powerful, modern alarm bell.

When a child is abducted, every second counts—and every decision matters. AMBER Alert is an early warning system that activates an urgent bulletin to galvanize community support and bring a missing child home. It is a powerful, modern alarm bell. The Navajo Nation brought a nine-month-old baby safely back to his mother after issuing its first Endangered Missing Person Advisory. The Department of Emergency Management issued the advisory for Nickolias Elias Tom on September 26 after his non-custodial father took him and authorities determined the baby was in danger. The advisory was issued at 7:13 a.m. and the baby was found safe by 5:14 p.m. The public and members of the media who signed up to receive the advisories were notified by text messages. Navajo officials said the new advisory is free, quick and worked flawlessly.

The Navajo Nation brought a nine-month-old baby safely back to his mother after issuing its first Endangered Missing Person Advisory. The Department of Emergency Management issued the advisory for Nickolias Elias Tom on September 26 after his non-custodial father took him and authorities determined the baby was in danger. The advisory was issued at 7:13 a.m. and the baby was found safe by 5:14 p.m. The public and members of the media who signed up to receive the advisories were notified by text messages. Navajo officials said the new advisory is free, quick and worked flawlessly. Be sure to check out the newly launched AMBER Alert in Indian Country website. The site offers a comprehensive array of resources, training and technical assistance information, and the latest news about the efforts and outcomes of AMBER Alert in Indian Country initiatives. You can visit the site at

Be sure to check out the newly launched AMBER Alert in Indian Country website. The site offers a comprehensive array of resources, training and technical assistance information, and the latest news about the efforts and outcomes of AMBER Alert in Indian Country initiatives. You can visit the site at

The Navajo Nation can now issue its own AMBER Alerts when a child is abducted on tribal lands. The AMBER Alert system is in effect for the eleven counties that cover the reservation in Arizona and Utah.

The Navajo Nation can now issue its own AMBER Alerts when a child is abducted on tribal lands. The AMBER Alert system is in effect for the eleven counties that cover the reservation in Arizona and Utah.

Casey Jo Pipestem was raised in Oklahoma City as a member of the Seminole Tribe. Casey’s grandmother raised her until she passed away when Casey was just 7 years old. She then lived with other relatives, but found it difficult to fit in while living in rural communities.

Casey Jo Pipestem was raised in Oklahoma City as a member of the Seminole Tribe. Casey’s grandmother raised her until she passed away when Casey was just 7 years old. She then lived with other relatives, but found it difficult to fit in while living in rural communities.