A growing threat in online grooming and “sextortion” prompted the United Kingdom’s National Crime Agency (NCA) to take action. After tech companies reported more than 9,600 cases of adults grooming children online in just six months—the equivalent of about 400 a week—the NCA launched what it called “unprecedented” public awareness campaigns. The campaigns alert U.K. teachers, parents, and children to the dangers of sextortion, in which victims are blackmailed into sharing abusive, explicit images. The British newspaper The Guardian outlined how widespread the threat is. The National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC) noted a 192% increase from 2023 in reports from tech firms of adults across the world soliciting children. Law enforcement agencies are increasingly concerned that predators are finding more sophisticated ways to target children online. A lengthy manual giving detailed instructions on how best to exploit young Internet users was uncovered on online networks encouraging young men to commit crimes. That sextortion guide was allegedly produced by an Arizona man, whom the FBI arrested in late 2024.

By Jody Garlock

It’s an early morning in March, and about 100 law enforcement officials, social services professionals, legal experts, and others are gathered in a hotel ballroom in Latham, New York. Wearing lanyards with name tags and sitting at tables with laptops and papers in front of them, they seem poised for a routine conference. But there’s a seriousness in the air and laser focus as they work on their computers or huddle into small groups.

Eventually, the ringing of a bell sounds across the room. Heads turn toward a man holding a brass school bellas the realization sets in: A missing child has been located.

By the end of the three-day Capital Region Missing Child Rescue Operation, that bell will have been rung an impressive 63 times. Simultaneously, a computer screen projected onto a wall showed the number in big, bold lettering. Both served as uplifting motivators for the agencies and experts who united for a goal of finding missing children at risk of endangerment, exploitation, or harm. “After the first or second bell ring, everyone gets it—it’s powerful,” says Tim Williams, manager of the New York State Missing Persons Clearinghouse (NYSMPC), one of organizers. “You could feel the energy in the room continue to increase.”

More than 60 local, state, and federal law enforcement agencies, nonprofit organizations, and private partners came together to explore new leads, review case notes, and leverage technology to find at-risk youth reported missing as runaways.

The 63 children and teens located during the first-ever rescue operation for the Albany, Schenectady, and Troy areas ranged in age from 2 to 17 years old when they were reported

missing, and from 6 to 22 when found, according to the New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services (DCJS). And the overall number of those safely located continued to climb, as work that was started wrapped up after the event. Williams says 71 missing children have now been located as a direct result of the rescue operation.

“These are emotional events,” says Kevin Branzetti (shown below right under quote), CEO of the National Child Protection Task Force (NCPTF), which partnered with NYSMPC on the operation and has similar recovery missions scheduled in other states.

“We know these cases can be emotional roller coasters. You see a lot of tears.”

To drive home the importance of such ventures, Branzetti and Williams point to statistics. At the end of 2024, New York had slightly more than 1,000 active missing children cases. The majority of the 12,000-plus cases annually—95 percent— are reported as runaways.

“Every missing child is an endangered missing child,” Williams says. “Our focus was the runaway population because it’s often overlooked.”

Strategic Teamwork

The Capital Region event grew out of training sessions between NYSMPC and the Arkansas-based NCPTF. “We started to think ‘Could we put all these people in the same room with the sole mission of finding kids and closing cases?’ “ Williams says.

In October 2024, NYSMPC and NCPTF spearheaded their first joint rescue operation. That venture in the Buffalo area safely located 47 children reported missing as runways. Branzetti and Clearinghouse staffers, including Williams and Cindy Neff, who recently retired as NYSMPC manager, applied lessons they learned from the Buffalo operation. Comparatively, the Capital Region operation was more complex, involving coordination among three police departments, three district attorney’s offices, and three county social services agencies, along with many other entities.

“One of the most critical components is securing full buy-in from local partners, law enforcement, social services, district attorneys, and child advocacy centers,” Neff says. “Their collaboration is essential because these operations go beyond just locating missing youth. It’s also about understanding the underlying reasons they went missing and identifying the support needed to help prevent it from happening again.” (For more on Neff see the sidebar that follows this feature.)

The Capital Region operation required months of planning and meetings to review cases with agencies and coordinate logistics. Participants were ultimately organized into four teams— two for Albany and one each for Schenectady and Troy. A pre-operation meeting was held for all the teams prior to the operation.

Each team had a similar composition: a Clearinghouse representative who acted as the organizer, a crime analyst who had access to local police records, at least one detective from the agency working the case, representatives from NCTPF and the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC), a probation official, someone from social services, and various other law enforcement officials. The goal was to ensure that each team had a variety of resources and skill sets, be it public records searching, tracking a cell phone, understanding social media work, or open-source intelligence. “No two police departments have the same sets of tools,” Branzetti says. “Everyone brings their tools to the game, and we get to share them.”

Adding a social services component—and having those professionals in the room prepared to go out when a child was recovered—was one of the lessons learned from the prior operation. Branzetti, Williams, and Neff note that the goal wasn’t just to find the child, but also to try to ensure the child doesn’t go missing again. “What we promote deeply is ‘Find. Listen. Help,’ “ Branzetti says. “It takes more than police to do that. It’s a society problem.”

The state’s Office of Children and Family Services coordinated with nonprofit organizations and victim assistance programs to assist the investigations and provide services and support for recovered children. “There was a whole support-service side of this ready to go and available—and put into action many times,” Williams says. If a child already had an assigned case worker, that person was notified.

A unique component was providing gift cards to ensure a child or teen had essentials, such as food, clothing, or haircare services. In some cases, the gift cards became an outreach opportunity for the social services worker to schedule a follow-up to take a teen shopping. “We wanted her to see that something is different today,” says Branzetti, whose organization secured donations to provide the gift cards. “We wanted her to understand that this isn’t the same old story. It’s about changing the trajectory.”

Additionally, the rescue operation also helps destigmatize the word “runaway.” “It’s a matter of changing the mindset of what that means,” Williams says.

“Everyone in the room is getting a better sense of the word as they work on the cases and realize that we can’t treat a runaway as ‘I’ll get to it when I get to it’ and instead say ‘Let’s make sure we’re doing something.’ “

‘Remarkable’ Collaboration

Heading into the rescue operation, the organizers didn’t have a set goal for the number of children they wanted to find. “If we can find even one missing child, that’s a positive,” Williams says. Because team members had started pre-work, some of the cases were able to be swiftly closed. A side benefit, Branzetti says, is that the rescue operation helps broaden or hone skills, and participants leave with added knowledge they can apply to their own cases. “These rescue operations turn into partial training events,” he says. “You actually may be writing a first search warrant or doing a first cell tower dump, or someone is walking you through how to track an IP address. You can’t beat that.”

The organizers also note that it’s heartening to see the camaraderie develop on the mixed teams, where members typically start out the rescue operation as strangers.

Williams says the operation proved to him how beneficial it is to bring together diverse groups. “We all tend to fall into the silo that we’re comfortable in, but we hear so many times, ‘Oh I wish I had reached out to you sooner,’ ” he says. “Sitting down at the same table, talking through cases, and sharing resources that are available is so important. Don’t be afraid to have those difficult conversations or continue to talk weekly or monthly to stay on top of things.”

For Neff, the rescue operation was a gratifying culmination to her long career. “When professionals from different agencies are brought together in the same room with a shared mission,” she says, “remarkable things can happen.”

Every time a child runs away, it’s a cry for help. That child is screaming out for our help, and it’s our job to do something.

Empathy & Respect: Hallmarks of Cindy Neff's Child Protection Career

For Cindy Neff, the Capital Region Missing Child Rescue Operation was a fitting end to a long career of helping children. In April, Neff retired from the New York State Missing Persons Clearinghouse, where she worked for 20 years—the past 11 years as manager. “She’s a force of nature,” says Kevin Branzetti, CEO of the National Child Protection Task Force who worked with Neff on the New York rescue operations and various other initiatives.

Over the years, Neff has been a familiar face at national AMBER Alert symposiums, serving as an Associate for NCJTC-AATTAP. She also led the charge for establishing the New York State Cold Case Review Panel and developing the Find Them web application to support law enforcement working missing persons cases.

The issue of children with multiple missing episodes has always been close to her heart. In New York, about half of the missing children classified as runaways involve repeat episodes. Neff likens it to her personal experience of her mother being shuffled from one nursing home to another until she landed in a place where she was treated with compassion and dignity. Like with her mother, she feels runaway children are placed wherever there is an open bed, not necessarily where they will receive the care and services they need.

To address the issue, she helped form a statewide partnership that promotes a systems-based approach to supporting vulnerable children. This led to launching RIPSTOP (Runaway Intervention Program: Services, Training, Opportunity, Prevention), which identifies root causes and connects youth to targeted services. The hope is that RIPSTOP becomes a model for the state.

“I believe it represents the future of how we must address missing child cases: with empathy, data-driven solutions, and collaboration across systems,” Neff says. “We must reject the mindset of ‘They’re just a runaway—they’ll come back.’ Every missing child is at risk until proven otherwise, and every case deserves our full attention.”

In her immediate retirement, Neff is recharging and enjoying time with her grandchildren. She also plans to thoughtfully consider how she may stay involved in the field in the future. She encourages fellow Clearinghouse managers and AMBER Alert Coordinators to carry on the mission on behalf of missing children by setting clear goals, regularly assessing priorities, and building strong partnerships at every level. “This work cannot be done in isolation,” she says.

By Denise Gee Peacock

The 2025 National AMBER Alert and AMBER Alert in Indian Country Symposium, held February 25-26 in Washington, D.C., brought together nearly 200 state and regional AMBER Alert coordinators, missing person clearinghouse managers, Tribal leaders, and public safety officials from across the U.S. and its territories, including American Samoa, Guam, and Puerto Rico.

Presenters and speakers included more than two dozen subject matter experts in missing child investigations and rapid response teams, emergency alerting, law enforcement technology, and Tribal law enforcement. Special guests included four family survivors who shared their powerful stories—and lessons learned.

Also there to address participants was Eileen Garry, Acting Administrator of the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, and U.S. Representative Andy Biggs of Arizona’s 5th Congressional District and co-sponsor of the Ashlynne Mike AMBER Alert in Indian Country Act of 2018.

The annual collaborative learning event is funded through the DOJ’s Office of Justice Programs and administered by the AMBER Alert Training & Technical Assistance Program (AATTAP) and its AMBER Alert in Indian Country (AIIC) initiative, both affiliated with the National Criminal Justice Training Center (NCJTC) of Fox Valley Technical College.

The symposium’s goal is to engage participants in discussing current issues, emerging technology, and best practices for recovering endangered missing and abducted children. Another objective is to improve the process of integration between state, regional, and rural communication plans with federally recognized Tribes from across the nation.

For the second year we enlisted the event management app Whova to help attendees plan their days, share their thoughts, and connect with each other. In keeping with that, we’ll let participants do most of the talking as we share event highlights.

This conference is a testament to the power

of collaboration. We’re here to bridge gaps,

share best practices, and innovate.

We’re here to hear the voices of those

who have experienced the unimaginable;

to honor their strength and resilience.

Janell Rasmussen

Never forget the difference you make in a child's

life. Ours is hard work, and sometimes gets us down.

But remember my family’s story. And never lose your

passion for keeping children safe.

Sayeh Rivazfar

AMBER Alert and Ashlynne’s Law

both save lives. Thank you for ensuring

your communities are prepared to

respond to every parent’s worst nightmare.

U.S. Representative Andy Biggs

I will continue to push forward and spread

awareness, particularly about Indian Country,

hoping that one day jurisdiction and sovereignty

will not play a role in the search for a child.

And that every Tribe will have a plan

in place if an AMBER Alert ever

has to be activated.

Jada Breaux

Sayeh [Rivazfar] is an incredible mother, an incredible warrior. Hearing her story was captivating, humbling, and gut-wrenching. As a mother of two young boys, I found her story beyond impactful. It provided a tangible sense of just how urgent it was to return home and continue the work.

Kelsey Commisso

AMBER Alerts: To Activate or Not Activate was my absolute favorite session. Since I’m new to my position, it really made me think!

Whytley Jones

I’d never heard of the ‘Baby in a Box’ case [involving Shannon Dedrick], and the ending surprised me. I loved hearing the investigative lessons learned from it.

Michael Garcia

Pasco County, Florida, Sheriff’s Office Captain Larry Kraus did an excellent job in explaining the application, effectiveness, and obstacles of OSINT. He is super-smart and relatable to those of us who may be tech-challenged.

John Graham

Erika Hock did a great job of presenting the Charlotte Sena case. Her humility shown through, especially when sharing the searching mother’s criticisms [of their alerting process] … and how she’s looking to implement some of the mother’s suggestions.

Ana Flores

SYMPOSIUM OVERVIEW

The symposium featured 28 presentations and workshops on relevant and pressing topics within child protection—each meant to deepen attendees’ understanding of current challenges and solutions. Click here to see the full agenda and here to read the speakers’ bios.

FAMILY PERSPECTIVES

- Pamela Foster: Keynote speaker (parental/ AMBER Alert in Indian Country focus)

- Sayeh Rivazfar: Keynote speaker (abduction survivor/law enforcement focus)

- Noelle Hunter: Presenter (international parental child abduction focus)

- Desiree Young: Presenter (parental focus)

INVESTIGATIONS / RESOURCES

- AMBER Alert Coordination: Essential Resources

- Missing Persons Clearinghouse Managers

- National Center for Missing & Exploited Children Updates

- Search Methods in Tribal Communities

- Tribal Response to Missing Children

- U.S. Marshals Service Support for Missing Children

CASE STUDIES

- “Baby in a Box” (Shannon Dedrick / Florida)

- CART Response to Child Sex Trafficking (New Jersey)

- Charlotte Sena Campground Abduction (New York)

- Gila River Indian Community (Arizona)

ALERTING / TECHNOLOGY

- AMBER Alerts: To Activate or Not Activate?

- FirstNet Authority Updates & Resources (Indian Country)

- IPAWS Emergency Communications Updates

- Open-Source Intelligence (OSINT) Analysis

CHILD ABDUCTION RESPONSE TEAMS (CARTs)

- Pasco County, Florida

- State of New Jersey

Knowing that Pamela Foster's daughter, Ashlynne Mike, loved butterflies, AATTAP Administrator/NCJTC Director Janell Rasmussen presented Foster with a meaningful gift. The sterling silver necklace features a butterfly with the name “Ashlynne Mike” intricately cut into its wings. The necklace was crafted by AATTAP-AIIC Project Coordinator Alica Murphy Wildcatt, a member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians.

Sayeh Rivazfar stands with a career shadowbox bequeathed to her by Florida Sheriff's Deputy Randy Mitchell. Mitchell had worked to see justice served after Sayeh was brutally assaulted and her sister, Sara, was murdered by a family friend in 1988. Mitchell was proud of Sayeh's decision to go into law enforcement.

AATTAP Deputy Administrator Jenniffer Price-Lehmann, left, introduces Dr. Noelle Hunter before her powerful presentation on international parental child abduction (IPCA). Hunter's 4-year-old daughter, "Muna," was illegally taken by her non-custodial father to West Africa. She ultimately was able to return home, but only after a "full court press" by Hunter and others to make that happen.

Learning From Survivors: A Top Theme

Sayeh Rivazfar’s life was forever changed on September 22, 1988. That was when her mother’s boyfriend took her, then age 8, and her 6-year-old sister Sara, from their home in Pensacola, Florida, drove them to a remote area, brutally assaulted them, slashed their throats, and left them to die. Sayeh survived; her sister did not.

While living with her father and brother in Rochester, New York, Sayeh chose to join the New York State Police. She has since retired after two decades’ work, but her child protection work continues.

“I decided early on not to let trauma take me down. I use it as fuel to help others.”

Rivazfar displayed a shadow box that belonged to Santa Rosa County (Florida) Sheriff’s Deputy Randy Mitchell. When assigned to her case, the new father was outraged over the pain inflicted on her and her sister. He and Rivazfar kept in touch over the years. “He was proud of my law enforcement career,” she said.

Then, in 2012, shortly before he died of cancer, she received a package from him—his “career in a box,” including his badge and shield, along with a poignant letter. “It means the world to me, as he did.”

'All Abductions Are Local'

On New Year’s Day 2011, Dr. Noelle Hunter’s worst fear was realized: Her ex-husband had illegally taken their 4-year-old daughter to live in his home country of Mali, West Africa.

Thus began the college professor’s quest to have Maayimuna (“Muna”) returned to her—after nearly three years of “full-court press” work.

It’s now her mission to help others navigating the complex mire of international parental child abduction (IPCA).

As an AATTAP/NCJTC Associate, she also helps law enforcement understand how to best respond to IPCA cases. They also should understand this: “All abductions are local. The response a parent gets from that first call for help means everything.”

Pamela Foster: ‘Indian Country Needs AMBER Alert’

Pamela Foster—the mother of Ashlynne Mike, namesake of the Ashlynne Mike AMBER Alert in Indian Country Act of 2018—was introduced to Symposium attendees by U.S. Representative Andy Biggs of Arizona’s 5th Congressional District. Biggs worked with Foster, and Arizona Senator John McCain to ensure passage of “Ashlynne's Law” two years after her 11-year-old daughter’s abduction and murder on the Navajo Nation reservation in 2016.

The Act provides numerous resources to Indian Country to bolster Tribal knowledge, training, technology, and partner collaboration to ensure children who go missing from Native lands can be found quickly and safely.

“Those of you in Tribal law enforcement, if you haven’t already received training, please schedule it as soon as possible,” Foster said. “We need law enforcement on Tribal land to share information with outside agencies so they can quickly apprehend criminals. Every child has the right to feel safe and live life to its fullest, and my fight is based on what I have experienced as a mother and a parent. I don’t ever want what happened to me to happen to another person.”

Foster’s powerful presentation was a gift to all who experienced it. Then she was given a gift—which provided another moving moment.

Read about Pamela's message, and the gift in honor of Ashlynne, here.

From Resources to Technology: More Takeaways

Click each dropdown box below for highlights from top-rated workshops & events.

“We’re good at hunting down fugitives. We’re now putting that toward finding missing children. It’s not something we’re known for. But we want to focus our efforts on kids with the highest likelihood of being victimized, of facing violence.” – Bill Boldin, Senior Inspector/National Missing Child Program Coordinator, U.S. Marshals Service (USMS)

Proven track record: From 2021 to 2024, 61% of missing child cases were resolved within seven days of USMS assistance.

“Mandates are pathways to support.” – Stacie Lick, Captain (Ret.), Gloucester County (New Jersey) Prosecutor’s Office

Having a dedicated, well-trained child abduction response team (CART) is essential to finding a missing child, using all available resources, when every minute counts. But symposium-goers know that building and sustaining a CART are significant obstacles for agencies with slim staffs and budgets.

The CART experts from New Jersey and Florida who shared advice at the symposium have spent nearly two decades overcoming those challenges by thinking creatively and strategically, such as getting buy-in for the expansion of New Jersey's CARTs after the high-profile Autumn Pasquale case in 2012. Or by having a well-thought-through staffing and resource plan, one that can be applied multi-jurisdictionally.

As a result of Captain Stacie Lick’s efforts to compile CART best practices for Gloucester County, New Jersey now mandates that all 21 of its counties have an active CART that follows standardized policies and procedures, and learns from mandatory after-action reporting. In 2008, as Lick was building Gloucester County’s CART, she was greatly inspired by the Pasco County, Florida, Sheriff’s Office (PCSO) Missing Abducted Child (MAC) Team.

Each MAC deploys with a command post with a lead investigator assigned to it. It also has coordinators assigned to these critical tasks: leads management; neighborhood/business canvassing and roadblocks; sex offender canvassing; resources oversight; volunteer search management; search and rescue operations; logistics; public information and media relations; crime scene management; legal representation; analytics; and cybercrimes/technical support. A family liaison and victim advocate will also be on hand to provide valuable assistance.

MODEL MANUALS

Many of the best practices used by the New Jersey and Pasco County, Florida, CARTs can be found in two newly updated, downloadable CART resources—one on implementation and the other on certification—both produced by AATTAP.

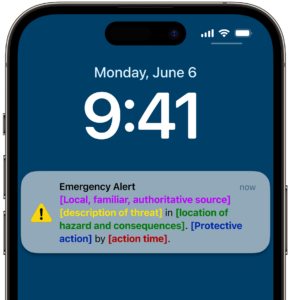

Law enforcement technology consultant Eddie Bertola provided several updates related to the Integrated Public Alert & Warning System (IPAWS) overseen by the Federal Emergency Management System (FEMA).

The IPAWS portal that law enforcement uses to request AMBER Alerts now has a more streamlined interface. And within that is the new Message Design Dashboard (MDD), “an intuitive structure taking message crafting from 15 minutes to five minutes,” Bertola said.

MDD features drop-down menus that provide access to essential information that can be provided in a consistent manner and allow best usage of the 360-character limit within varied templates. It also can check for typos and invalid links and allow for easier message previews and system testing.

In other messaging news, another development is the Missing and Endangered Person/MEP Code, which was discussed in both the IPAWS workshop and updates session hosted by the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC).

Approved in August 2004, the addition of the MEP code to the Emergency Alert System (EAS) will enable law enforcement agencies to more rapidly and effectively issue alerts about missing and endangered persons by covering a wider range of ages and circumstances than AMBER Alerts alone. MEP alerts will utilize the same infrastructure as AMBER Alerts, thus allowing for widespread dissemination through various media channels.

Open Source Intelligence (OSINT) analysis is the leveraging of data from publicly available communication sources such as social media apps, messaging boards, gaming platforms, and the dark web. This research complements more traditional law enforcement databases (criminal databases, LInX, LeadsOnline) and can yield more real-time clues.

Bad actors are increasingly digital obsessed—and inadvertently work against themselves by taking photos and videos with geolocations and time stamps—while leaving other digital breadcrumbs.

OSINT analysts requires continuous training on ever-evolving information-sharing channels. They need to understand how to avoid gleaning intelligence that can be challenged in court (and potentially weaken public trust). All the while they have to battle data overload from the sheer volume of information that needs assessing.

It’s imperative that agencies hire professionals capable of navigating such complexities, Kraus said of intelligence analysts, whom he calls “the unsung heroes of law enforcement.”

“I can’t believe I didn’t know about the Lost Person Behavior resource,” one attendee said on Whova. Mentioned during Pasco County’s CART workshop, “LPB,” as its known for short, refers to the science- and data-based research of Dr. Robert J. Koester, whose field guide-style book outlines 41 missing persons categories and provides layers of behavior a person in each classification will likely follow.

• Look afield: Re-open a case involving a long-term missing person, or one with unidentified human remains, and let the growing realm of reputable DNA labs help solve a crime once thought unsolvable. “Our labs are overworked, so we need to find more ways to use private ones,” O’Carroll said.

• “Prevent tomorrow’s victim by solving today’s case today,” O’Carroll said. Know the latest technology, including Rapid DNA, an FBI-approved process that can provide a scientific correlation in as little as 90 minutes.

This was the second year for AATTAP Region 1 Liaison and alerting veteran Joan Collins to teach the popular class designed to help attendees analyze real-world cases of missing children and AMBER Alert requests, noting the key factors within the criteria that determine when an alert is issued; evaluate AMBER Alert effectiveness by comparing case details with activation criteria and assessing factors that influence decision-making; and propose improved response strategies.

Collins’ style is to amiably pepper participants with more than a dozen widely varying missing child scenarios, often throwing daunting updates into the mix. Participants responded using the Poll Everywhere app, which tabulated their responses in real-time on a large viewing screen.

“The alerting sessions instill confidence in new AMBER Alert Coordinators as well as seasoned ones,” Collins said. “The scenarios spark vigorous discussions, and networking with fellow AACs underscores the fact that they all go through the same process, even if criteria may differ.”

TikTok is teaming up with the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC) to bring critical, time-sensitive information directly to people’s “For You” feeds. The goal is to raise awareness of missing children and leverage the power of the U.S. TikTok community to help reunite missing children with their families. The project was piloted in Texas from January to December 2024, when AMBER Alerts were viewed more than 20 million times and contributed to 2.5 million visits to NCMEC’s website. The AMBER Alerts will now reach more than 170 million Americans.

“The collaboration of effort in this case can’t be overstated.” So said U.S. Marshal Pete Elliott of an international search that led to the safe recovery of two missing children located in Iceland, some 3,000 miles away from their Ohio home. A family member who reported the 8- and 9-year-old missing in October 2024 indicated their mother had mental health issues and had stopped taking her medication. The ensuing three-month search included the U.S. Marshals Service, State Department, Interpol, and local police departments. The mother took the children to New York and Vermont before being tracked to Denver, Colorado, London, England, the Island of Jersey in the English Channel, a remote fishing village in Iceland, and finally to the capital city of Reykjavik, where local authorities located them in a hotel. Elliott said recovering children abroad is “extremely difficult,” and credited dedicated law enforcement officers for their work. After the children were placed in the care of social services, the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children provided financial support to reunite them with family in the U.S. The mother was recovering in a hospital.

By Denise Gee Peacock

On New Year’s Day 2011, Dr. Noelle Hunter was approaching hour three of waiting in a Morehead, Kentucky, McDonald’s—the agreed-upon meeting place for her ex-husband to return their 4-year-old daughter, Maayimuna (“Muna”)—when she knew something was terribly wrong.

Little did she know Muna’s father had taken her 5,000 miles away to live with his family in their native country of Mali, West Africa, despite Dr. Hunter, having been granted sole custody of her.

While it took more than three years for Hunter to get Muna home, during that time the university professor would learn so much: Chiefly, just how much understanding law enforcement needs to know about the complexities of international parental child abduction (IPCA)—the proactive efforts needed to avoid it, and quick actions necessary to stop it in its tracks.

Hunter’s journey of IPCA understanding began with her local police department. “They told me my problem was a civil matter, a domestic dispute; that I needed to get a court order before they could do anything,” she shared with symposium-goers. “One good thing they told me was to contact the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC). And that’s when I learned that federal law mandates that any child under age 18 must be entered into the National Crime Information Center (NCIC) database within two hours of being reported missing.”

NCMEC reached out to Morehead authorities to inform them of their obligation to enter Muna into NCIC. They also advised Hunter to directly contact the FBI for assistance. After learning that Muna had indeed been taken to Mali, she was connected with the U.S. State Department.

Hunter learned her ex-husband had accomplished the abduction by obtaining a passport for Muna in Mali, where she had dual citizenship because of her father (“which I had never taken into account; I thought as long as I had her passport she would have to stay in the U.S.”) She also learned about the Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction (aka the Hague Abduction Convention), a treaty in which its signatories commit to returning abducted children to their rightful guardian. But while the U.S. is a signatory, Mali is not. They had no obligation to return Muna to her. And meanwhile, the country was in the throes of a government coup.

Desperate yet determined, Hunter immersed herself into a relentless “Missing 4 Muna” campaign to get her daughter home. She read everything she could about IPCA; talked with legal experts, many of whom offered to help her pro bono; navigated the cultural nuances of working with Mali officials; staged protests in front of Mali’s embassy in Washington, D.C.; pleaded with United Nations members; helped create a nonprofit organization to assist other IPCA families; and worked with a congressional delegation from Kentucky to pressure the Mali government to safely return Muna in 2014. By then she was almost 7.

Hunter now works as an assistant professor of political science and philosophy at University of Alabama in Huntsville, which houses the program she founded: the International Child Abduction Prevention and Research Office (ICAPRO). From there, she and her daughters—Muna and her sister, Rysa Lee, advocate for IPCA awareness and support.

“Most of the parents still seeking their children are committed to doing whatever it takes to bring them home. But as I learned, we can’t do it alone,” Hunter said. “That’s why I’m glad this symposium exists, and that all of you undertake full-court-presses of your own to help find missing children and get them home where they belong. Remember, all abductions are local.”

Sweet Memory: A Maryland State Trooper’s Compassion

During my mission to get Muna home from West Africa, I was constantly traveling from Kentucky, where I lived at the time, to Washington, D.C., knocking on every door I could. It was exhausting work. On one drive home, I was particularly distraught, and wasn’t really paying attention to my speed. So because I was speeding, I was pulled over by a Maryland State Trooper. He took one look at me, and said, “What’s wrong?” So I told him. Everything. He then started trying to help, asking if I’d talked with the U.S. State Department, if I’d done this or done that. I told him yes—I was doing everything I could.

At that point he said he wouldn’t write me a ticket, but added, “Promise me two things. That you’ll slow down and and get home safely. And that when your daughter returns home, make sure her first ice cream is courtesy of a trooper in Maryland.”

So that's what you see in this photo: that trooper’s gift to her—and me.

I think that’s significant at a conference like this. Please consider that local law enforcement support is crucial for a parent experiencing IPCA. A little grace never hurts either.

While searching for their missing child, parents carry a heavy load—assisting law enforcement, rallying media and public interest in the case, and working to keep food on the table—all while not completely unraveling. But another group of family members is also struggling: the missing child’s siblings.

As sibling survivor Trevor Wetterling recalls, “People would always ask, ‘How are your parents doing?’ And I’d think, ‘What about me? Don’t they care how I’m doing?’ ” Meanwhile, he says, “I’d come home from school, and everyone was sitting around being quiet. No one would tell me what was going on.”

Like other sibling survivors, Trevor’s feelings stem not from self-centeredness, but from a need to validate his own trauma, his own sense of worth.

Trevor is the brother of Jacob Wetterling, an 11-year-old who was kidnapped at gunpoint by a masked man in 1988. Trevor was with Jacob when the abduction occurred, making the ordeal even more traumatic. The Wetterling family spent nearly three decades searching for Jacob until 2016, when his killer divulged to law enforcement where the boy’s body could be found. This, of course, came as another blow.

Trevor and his sisters, Amy and Carmen, are three of 16 sibling survivors of missing children willing to talk candidly about the challenges they faced—and sometimes continue to reckon with. If struggling siblings are lucky, they’ll find support from well-trained professionals. If they’re even luckier, they’ll find strength from those who truly understand their needs: Fellow survivors—whom Zach Svendgard calls “our chosen family.”

Zack is the brother of Jessika Svendgard, an honor student who, at age 15, left home after receiving a bad grade. Alone and vulnerable, she was lured into the hands of sex traffickers until she could break free from her abusers. Zack appreciates Jessika’s strength—and works to share it. “The world is a heavy thing to try to balance all on our own shoulders,” he says. “But powerful things can happen when kind people are enabled to take action.”

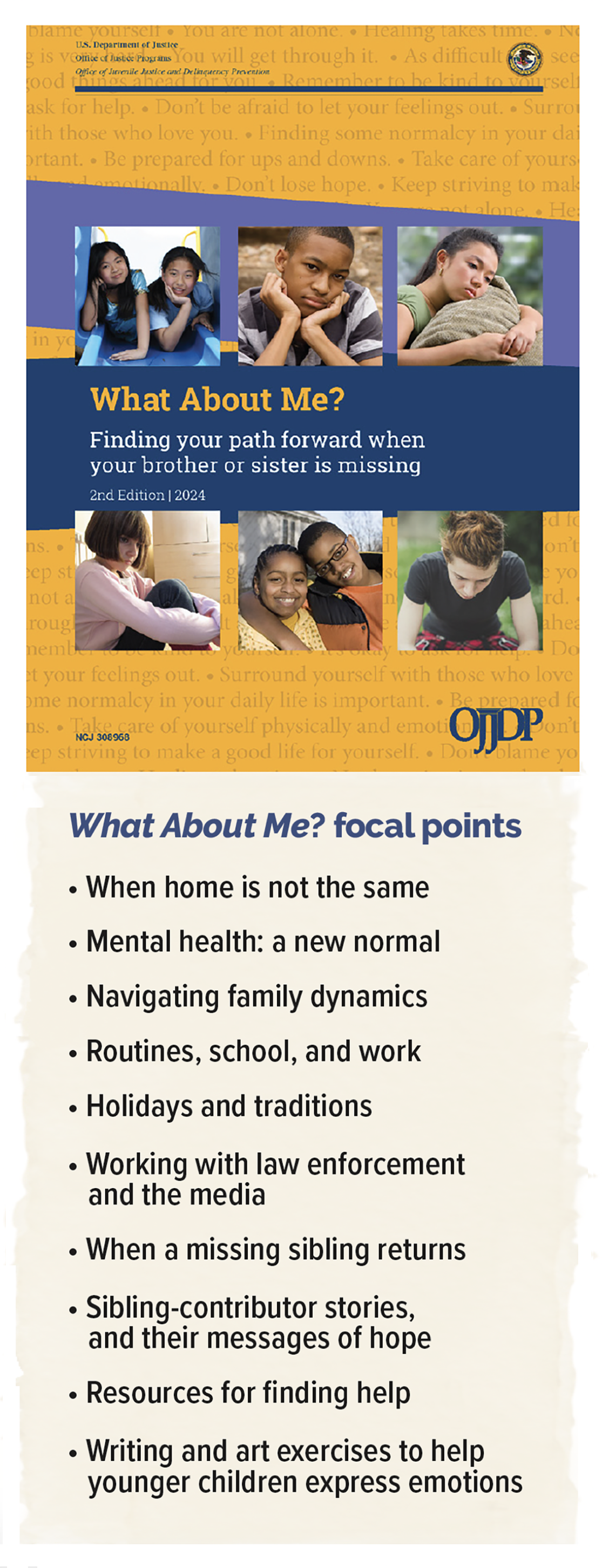

The new 98-page What About Me? is the second edition of a guide first published in 2007. It was spearheaded by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP) / Office of Justice Programs (OJP) of the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ). Its development was overseen by the AMBER Alert Training & Technical Assistance Program (AATTAP) / National Criminal Justice Training Center (NCJTC) of Fox Valley Technical College.

Contributors to What About Me? bring clarity to the complex needs siblings face: Children in families with missing siblings can’t easily process what they’re experiencing. They aren’t hearing the particulars from law enforcement. They aren’t trained to respond to an intrusive or hurtful question from the media. They don’t know how to navigate their frayed family dynamics. And they need help.

The guide provides tangible ways that siblings of missing children can handle stress, the investigative process, and media interactions. It also can help them express their needs to their loved ones and family advocates, and find helpful resources during either a short or prolonged period of uncertainty, fear, and grief.

What About Me? features the voices and perspectives of eight sibling contributors while weaving in advice from seven other siblings who participated in the first edition. It also reflects the expertise of DOJ/AATTAP/NCJTC subject matter experts, child/victim advocates, and relevant, credible U.S. agencies that can help.

The sibling contributors have survived vastly different experiences: Some have missing siblings who were kidnapped by strangers or abducted by family members, while others have siblings who ran away or were lured away from home. Some of their siblings were found safe and returned home. One contributor is herself a victim of a horrific abduction and assault—in which her younger sister was murdered. Others have siblings whose whereabouts still remain unknown, or they were found deceased.

To produce What About Me?, OJJDP/OJP tapped the AATTAP publications team led by Bonnie Ferenbach, and NCJTC Associate Helen Connelly to coordinate the project. The group also played key roles in updating When Your Child Is Missing: A Family Survival Guide, released in 2023.

Connelly is a longtime advocate for missing children and their families. In 2005, while serving as a senior consultant for the U.S. Department of Justice, Connelly and Ron Laney, then Associate Administrator of OJJDP’s Child Protection Division, teamed up to produce the first-ever sibling survival guide, What About Me? Coping With the Abduction of a Brother or Sister, published in 2007.

“Through Helen and Ron’s vision and compassion, this guide, as well as numerous other resources, have provided support, encouragement, help, and resources needed by so many families,” says AATTAP Administrator Janell Rasmussen.

With Connelly’s encouragement, past and present sibling contributors participated in writing the guide because they recognize shared pain—and potential dilemmas. “Trauma, if left untreated, can manifest itself in harmful ways later in life,” says sibling contributor Heather Bish.

The sibling survivors who worked on the updated resource valued the chance to collaborate with others in “the club nobody wants to belong to,” says Heather, who contributed to both editions. “But our experiences are special,” adds contributor Rysa Lee. “We have the tools that can help others.”

At the project’s start, the siblings met virtually before gathering in person in Salt Lake City in January 2024. There, they bonded, and wholeheartedly shared their experiences and advice on camera for the new edition’s companion videos. “Working with the other siblings of missing persons left me shocked at the outcomes they had; in some way, they each had answers,” says contributor Kimber Biggs. “It was comforting to know that getting answers is even possible.”

Content talks continued, and the guide began to take shape. Then, on May 22, 2024, a powerful two-hour roundtable was held at OJJDP offices after the National Missing Children’s Day ceremony in Washington, D.C.

The siblings agree that “there is no right or wrong way to survive, it is just our own,” Heather says. “We hope that sharing our experiences will empower other siblings to forge ahead, and possibly empower someone else to do the same.”

Sayeh doesn’t think of herself as a victim or survivor: “It’s more than that. I see myself more as a thriver, despite the odds.” She credits this to the love and support she has received over the years from family members, friends, and caring professionals.

“A guide like this would have been so helpful to us,” she says. “But we hope that now, with its help, with our help, children can know they are not alone. That we care about them, and want them to thrive too.”

Rysa adds another positive take. There is light to be found in the darkness of tumult, she says. “Siblings do come home, and my family is living proof.”

New guide’s sibling contributors

Rysa Lee, sister of Maayimuna “Muna” N’Diaye (Alabama) Rysa was 14 when her 4-year-old sister, “Muna,” was abducted by her biological father to Mali, West Africa, on December 27, 2011. Rysa and Muna’s mother, Dr. Noelle Hunter, began a relentless campaign to bring “Muna” home—which thankfully occurred in July 2014. Since then, the family has tirelessly advocated on behalf of international parental child abduction (IPCA) cases via the organization they founded, the iStandParent Network. While her sister’s IPCA case was relatively short, “that year and a half was by far the most difficult and longest time of my life,” Rysa says. “To this day, I have never felt as empty and distraught as I felt during that time. The fact that my youngest sister was across an ocean and not in the room next to me sleeping every night was incredibly painful.” Rysa found comfort in high school band and color guard participation, listening to music, “and leaning on my friends to cope.” She currently works in banking and attends the University of Alabama in Huntsville, where her mother, an assistant professor of political science, oversees the International Child Abduction Prevention and Research Office (and contributed to the Family Survival Guide).

Cory Redwine, brother of Dylan Redwine (Colorado) On November 18, 2012, Cory was 20 years old when his 13-year-old younger brother, Dylan, traveled to stay with their father on a scheduled court-ordered visit. The next day his father would report Dylan as missing. The teen’s whereabouts remained unknown until 2017, when his father was convicted of second-degree murder and child abuse in Dylan’s death. Before then, Cory and his family spent nearly a decade searching for Dylan. They have since spent years seeking justice for him and educating others about the legal loopholes in parental custody issues that can prove deadly. (Cory and Dylan’s mother, Elaine Hall, is now an AATTAP/ NCJTC Associate who discusses her family’s case with law enforcement; she also contributed to the Family Survival Guide.) Cory recalls the court process being “long and arduous; it brought up so many emotions for me. But it also made me realize that I am stronger than I thought I was, that my voice and words are powerful,” he says. Now a father of two, Cory finds it an honor to helps adults facing difficult situations. “My experience, different as it is from theirs, allows me to help them through challenging times and come out better on the other side.”

Sayeh Rivazfar, sister of Sara Rivazfar (New York) After her parents’ divorce in 1985, Sayeh and her younger siblings had “child welfare officials in and out of our home due to physical and mental abuse at the hands of our mother and others,” Sayeh says. “Unfortunately, [our mother] thought having men in our lives would help us. But her boyfriends weren’t all good. In fact, one changed our lives forever in the worst way imaginable.” In the middle of the night of September 22, 1988, one of those boyfriends took the sisters from their home, drove to a remote area, brutally assaulted both girls and left them to die. Sayeh, then 8 years old, survived. Sara, age 6, did not. “From that day forward, I felt guilty for surviving and had dreams of saving my sister from this nightmare,” Sayeh says. “I was determined to bring her killer to justice.” Thankfully she was able to do just that. She and her brother, Aresh, moved to Rochester, New York, to live with their father, Ahmad (now a nationally known child protection advocate and Family Survival Guide contributor). Sayeh’s passion to help others, especially children, inspired her to join the New York State Police force, from which she recently retired after two decades of child protection and investigative work. She now focuses on being a good mother to her son. “I’m proud of the work I’ve done, and even prouder of the children I’ve helped,” she says. “The story never ends, but it can have a better ending than one might think.”

Heather Bish, sister of Molly Bish (Massachusetts) On June 27, 2000, Heather’s 16-year-old sister, Molly, went missing while working as a lifeguard. Molly’s disappearance led to the most extensive search for a missing person in Massachusetts history. In June 2003, Molly’s remains were found five miles from her home in Warren. While the investigation into her sister’s murder continues, Heather uses social media to help law enforcement generate leads and “share her story—our story,” she says. Heather was supportive of her parents’ work to create the Molly Bish Foundation, dedicated to protecting children. “I carry that legacy on today,” she says. She has filed familial DNA legislation for unresolved cases and advocates for DNA analyses for these types of crimes. She also has served on the Massachusetts Office of Victim Assistance Board and was part of the state’s Missing Persons Task Force. “As a mother and a teacher, my hope is that children never have to experience a tragedy like this.”

Zack Svendgard, brother of Jessika Svendgard (Washington) In 2010, Zack’s younger sister, Jessika, first ran away, and then was lured away from their family home near Seattle. As a result, the 15-year-old became a victim of sex trafficking. It took 108 days for Jessika to return to her family and get the help she needed, Zack says. “Her recovery in many ways was just the beginning. In many ways the broken person who came home was not the little girl who had left.” Jessika’s ordeal has been featured in the documentaries “I Am Jane Doe” and “The Long Night.” She and her mother, Nacole, have become powerful advocates for victims of sex trafficking and instrumental in passing legislation to increase victim rights, issue harsher punishments for sex offenders, and shut down websites that facilitate sex trafficking. (Nacole is an AATTAP/NCJTC Associate who provides her family perspective to law enforcement; she also contributed to the Family Survival Guide.) “We’ve joined organizations such as Team HOPE [of the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children/NCMEC] to provide counseling to others, and are ourselves committed to therapy and self care.”

Amy & Carmen Wetterling, brother of Jacob (Minnesota) On October 22, 1989, Amy and Carmen’s brother, 11-year-old Jacob, was abducted at gunpoint by a masked man while riding his bike with his younger brother, Trevor, and a family friend. His whereabouts were unknown for nearly three decades, but on September 1, 2016, Jacob’s remains were found after his killer confessed to the crime. Jacob’s abduction had an enormous impact—not only on his family, but also on people throughout the Midwest, who lost their sense of safety. Amy, Carmen, and Trevor have been inspired to help others by their mother, Patty Wetterling. Patty has shared countless victim impact sessions with law enforcement across the U.S. (many of them AATTAP/NCJTC trainings). She is co-founder and past director NCMEC’s Team HOPE, co-author of the 2023 book, Dear Jacob: A Mother’s Journey of Hope, and a contributor to the Family Survival Guide. “Jacob inspires us every day,” Amy says. “He believed in a fair and just world, a world where all children know they are special and deserve to be safe.” Adds Carmen, “Jacob believed that people were good. And he lived his life centered on 11 simple traits.”

Additional contributors:

Learn about the siblings who shared their advice for the 2007 first edition of What About Me? Coping With the Abduction of a Brother or Sister here.

![Sibling contributor Sayeh Rivazfar—a retired 20-year veteran of the New York State Police—with her son. [Photo: MaKenna Rivazfar]](https://amberadvocate.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Sayeh-Rivazfar-and-little-boy-makenna-rivaz-copy.png)

Helpful advice for the helpers

What About Me? includes a detailed section of guidance relating to law enforcement and judicial processes. It also provides tips for navigating traditional media and social media. Consider these insights from the sibling contributors.

During a law enforcement investigation

- Siblings “may have a law enforcement officer with little or no experience with a missing children case, seems uncomfortable and distant, or someone who jumps in with both feet,” says Sayeh Rivazfar. The retired law enforcement professional is the survivor of a heinous crime against her and her sister, Sara, who did not survive. “If you want to talk to a different officer, speak up,” Sayeh advises.

- Children are especially confused by law enforcement’s intrusion upon their home and being asked what seems like invasive questions. Help them understand that this is normal—either directly or with the help of a family/child advocate.

- “Just because you don’t hear about progress doesn’t mean they’re not making any,” one sibling notes. Try to schedule regular check-in calls with the family. Let families know that while law enforcement is unable to share every detail of the investigation, they can strive to apprise the family of their progress while keeping lines of communication open and productive.

- If children are expressing anger toward their parents, emphasize that “your parents are still your parents, they still love you, and they care about your feelings—even if they can’t show it right now,” contributors say.

- Be prepared for such questions as:

»How do I handle phone calls during the search?

»How should we handle our missing sibling’s social media and email accounts?

»Can I still go into my sibling’s room?

»Will we get their belongings back?

Working with traditional/social media

- There’s no such thing as “off the record,” contributors say.

- To foster quality reporting “find the journalist who provides compassion and truth, and give them an exclusive interview,” Sayeh advises.

- With nonstop anonymous, uniformed sources on social media, tell children to “be prepared for positive and negative running commentary,” Rysa Lee says.

- Propose potential answers (in italics) to commonly asked media questions that often make children uncomfortable:

»Do you think your sibling is still alive? I hope so.

»What happened? I don’t know, and I don’t want to talk about it with you.

»Was your sibling sexually abused? I don’t know, but it’s not something I want to discuss.

»How does this situation make you feel? I don’t want to talk about my feelings right now.

By Jody Garlock

Deputy Wes Brough has been in law enforcement for what he matter-of-factly describes as “a crazy” five years. In that short time with the Volusia County Sheriff’s Office in DeLand, Florida, he has worked AMBER Alerts, saved a teen who was contemplating jumping off a bridge, and, most recently, been hailed a hero for rescuing a missing 5-year-old boy with autism.

In the latter case, the dramatic body-cam footage of Brough running into a large pond to carry the missing child to safety put him in a national spotlight after the video went viral—and showed how dangerously close the story was to a sad outcome.

That August 2024 day remains fresh in his mind. Brough (pronounced “Bruff”) was on routine patrol in Deltona (in east-central Florida) when a 911 call reporting the child missing came in—a call he and other officers were able to hear in real time thanks to a new telecommunication system.

After hearing of a possible sighting of the child behind a nearby home, Brough’s autism awareness training kicked in. Knowing that area had wooded wetlands and that children with autism are drawn to water, Brough took off running. Hurling tree debris and calling the boy’s name as he approached a nearby trail and pond, the breathless deputy would momentarily stop to look for any signs of movement in the water or footprints on the swampy ground.

At first Brough didn’t see any signs of the child. But then the boy, who is nonverbal, made a noise, likely after noticing Brough through the trees. The deputy ran toward the sound, and after spotting the boy in the pond, yelled, “I got him! I got him!” as he ran into the near-waist-high water where the 5-year-old was holding on to a branch. He would soon cling safely to Brough as they made their way back to land. There, as darkness neared, medics checked the boy’s health before he was reunited with his frightened family. The swift recovery was completed about 20 minutes after the 911 call that reported the child missing.

We talked with Brough about the incident and the lessons it may hold for others in law enforcement.

How does it feel to be called a hero?

That’s a big title honestly—especially when anybody in my position would have done the exact same thing. I’m very honored, but I’m staying humble and giving the glory to God for helping me do the right thing in the right moment.

What type of training helped prepare you for such an incident?

We have critical incident training when we come through the sheriff’s office, and it focuses on different types of behavior. We also go through autism awareness training which includes meeting with children with autism and their families who live in our community; it’s very in depth. It covers the dangers a child with autism can face, and understanding the biggest cause of death: drowning. That’s a big factor here in Florida, where there’s so much water. We learn how to interact with children with autism and the different levels of the autism spectrum. We also look at different scenarios that we in law enforcement might face, whether it’s responding to a runaway child or a suspicious person. You never know when the person you’re interacting with may have autism, so being aware, and picking up on social cues, is important.

Are there ways to better engage the public about missing autistic children?

There’s always room for more communication between an agency and the public, especially on a subject like this. An easy way is through social media posts. Also, parents should be encouraged to never hesitate to call 911 if their child goes missing. The boy’s family did a wonderful job of calling as soon as they heard the alarm on their door go off. We’d rather have the call get canceled on the way to search for a missing child instead of being 20 minutes behind the curve.

What lessons did you learn that others could apply—what are your takeaways?

One, a lot of good work gets done when you stay calm under pressure. And two, it’s important to have a sense of urgency. Too often complacency can kick in; you think a missing kid may be at a friend’s house or hiding in a shed. You might walk rather than run. When I picked up the log the boy was holding onto in the water, it broke in half. It was only a matter of time before it broke while he was holding on to it, or that he went out deeper into the water. Hindsight is 20/20, but I’m glad I had the sense of urgency to run from the road to the pond. It was moving with a purpose. There can’t be hesitation when the priority is someone’s life.

Calling it one of his agency’s “most sacred missions,” U.S. Marshals Service Director Ronald L. Davis vowed that recovering the nation’s critically missing children will remain a top priority. His comment came on the heels of a nationwide operation that recovered 200 missing children, including endangered runaways and those abducted by noncustodial parents, deemed at high risk for danger. The May-June “Operation We Will Find You 2,” the second of its kind, brought together federal, state, and local agencies; the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC) provided technical assistance. The search led to the recovery and removal of 123 children from dangerous situations. An additional 77 missing children were found to be in safe locations. NCMEC President and CEO Michelle DeLaune said the effort is a “shining example of the results we can achieve when we unite in our mission to find missing children.”

The growing use of generative artificial intelligence (GAI) is raising concerns about the dangers it poses to child safety, with the Internet Watch Foundation calling it a potential “playground for online predators.” Pedophiles and bad actors are using GAI to manipulate child sexual abuse material (CSAM), with a child’s face transplanted onto the footage, or to create deepfake sexually explicit videos using an innocent photo of a real child. IWF expects more—and higher quality—CSAM videos to emerge as the technology grows. The group is pushing for controls, such as making it illegal to create guides on generating AI-made CSAM. The National Center for Missing & Exploited Children is also pushing for updates in federal and state laws pertaining to GAI CSAM. Additionally, AI-made CSAM is reportedly overwhelming law enforcement’s ability to identify and rescue real-life victims.

In 2023, the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC) CyberTipline received a staggering 36.2 million reports of suspected child sexual exploitation. To counter that, a chilling new interactive video, “No Escape Room,” uses dozens of real-life tipline scenarios to immerse parents and caregivers into a child’s online world, often fraught with peril. Throughout the experience, users are prompted to engage in a conversation with someone they think is another teenager. The friendly, flirtatious chat soon involves requests for nude or sexually explicit photos, eventually trapping the child in a blackmail scenario. The video’s immersive viewpoint shows parents firsthand how children are targeted by predators and struggle to navigate dangerous circumstances. At the end of the experience, users are directed to NCMEC’s resources on sextortion.

Michael Jude Nixon’s middle name is his mother’s homage to Saint Jude, “the patron saint of hope and hopeless causes,” Nixon says. “She had a rough time during her pregnancy with me, and found comfort in prayer,” he says. “Thankfully everything turned out OK.”

And thankfully for those in his hometown of Beaumont, Texas, Nixon has devoted his life to serving people in need of hope—people facing hopeless causes.

“My family taught me to recognize a higher purpose in life,” says Nixon, who retired five years ago as a detective with the Beaumont Police Department, where he worked for almost 16 years and was the department’s AMBER Alert Coordinator.

Nixon now serves in two broader-ranging law enforcement capacities. Since 2020 he has held the role of Region 12 Missing Person Alert Coordinator for the Texas Department of Public Safety. (Region 12, comprising six counties in the Beaumont area, is home to about 500,000 people in southeastern Texas near southern Louisiana.)

Since 2020, Nixon has worked as Assistant Director and Training Coordinator for the Lamar Institute of Technology (LIT) Regional Police Academy in Beaumont. And on the national front, he recently joined Team Adam, a seasoned group of law enforcement professionals tapped for rapid deployment by the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children to investigate missing child cases.

Nixon’s path into law enforcement followed a decade of doing manual labor for the City of Beaumont.

The first half of that chapter was working in water maintenance for five years, and for the next five “dealing with alligators, snakes, you name it” as an animal control officer. The arduous, all-hours work “was difficult, but important,” he says. “It just didn’t pay enough to help me make ends meet” for his young family, and kept him from home a lot.

Some friends at the Beaumont Police Department encouraged him to join the BPD.

But then came Hurdle One. “Initially, I was provided a job offer, but it was rescinded after they learned I had a GED instead of a high school diploma.” (Nixon earned a GED at 18 after enlisting in the U.S. Army Reserve.) Undaunted, he returned to high school at age 32 and received that diploma. That allowed him to train at LIT and join the BPD in 2004.

Next came Hurdle Two: navigating the traumas associated with crimes against children—from child abuse to sex trafficking cases, which he was responsible for investigating for much of his BPD career.

The way he managed to cope (see “Take 5” section below) now informs his Regional Police Academy training work at LIT. It also has spurred him to continue expanding his horizons for both personal and professional growth. In December 2023 he earned his Associate of Science degree in criminal justice from LIT, and currently is pursuing a bachelor’s degree in the discipline from Lamar University.

We recently caught up with Nixon so we could learn more about his work experiences—and also glean his advice that others could apply to their work lives.

How did your world change after becoming a police officer? Working for the water department and as an animal control officer prepared me well. I saw the downside of humanity in those roles, and it was humbling. That makes you a more empathetic person. I was able to carry that over into law enforcement. I realized that everybody I encountered was somebody’s child, somebody’s parent, somebody’s loved one. I credit that to my mom’s influence. She taught me to be nice to people, even if you can’t do anything else to help.

What were some challenges you faced in your law enforcement work? Earning people’s trust, for one. Also, getting them to talk. Many small-town communities that have been mistreated or ignored by law enforcement have built up a wall, a mentality of ‘us versus them.’ That wall has to be continually torn down by both cops and citizens, Black and White alike. That’s because any national incident of police brutality will overshadow hundreds if not thousands of positive incidents, so it’s an uphill battle that we have to learn from. It doesn’t do us any good to be overzealous or condescending. As my mother always said, ‘You can catch more flies with honey.’ And when someone extends an olive branch, take it. I made an effort to go to park events and parades, to meet people on their level. We may not be welcomed at first—or the second time or third time—but we shouldn’t give up.

How did that affect cases involving missing children? When a community doesn’t trust law enforcement they’ll think they can solve a problem faster and more effectively on their own—of not getting the police involved. That’s especially true because most AMBER Alerts we handle are family-related and not stranger abductions, so people figure an outsider won’t be much help. I’ve had to work hard to convince them that I’m on their side. One challenge comes when children have been lured into sex trafficking. You have about four seconds to make a positive impression before they close their minds to you. Most have been told not to trust law enforcement; to be afraid that a cop will victimize them.

Do you cross paths with some of the children you helped over the years? I see a lot of them quite frequently, but very few know who I am. That’s by design; our child advocacy center is their true liaison. But their parents tend to know who I am. Often they’re people I grew up with. And sometimes they’ve come to me for guidance. I feel good when I can help.

Take 5: Ways to keep stress in check

Dealing with the disturbing realities of child protection work is a major stressor for law enforcement. “So many of us compartmentalize all the things we see,” Michael Nixon says. “We tell everybody that we’re fine when we’re not.” Here is some of his hard-won wisdom.

Leave work at work. “One of the best decisions I ever made was never talking with my family about any bad things that I had seen during the day. The boogeyman is not welcome at my house.”

Do a wellness check—on yourself. “Everyone—but especially those in law enforcement—should practice self-care,” Nixon says. “Find a way to step back, take a deep breath, and decompress. For instance, in an active shooter situation, we may run on adrenaline until there’s a break in the action. That’s when we’re supposed to check ourselves for wounds we may not be aware of. The same goes for investigating crimes against children. Check yourself every 12 hours to ensure you’re OK.”

Fortify your body and mind. “I found strength, and stress relief, by going to the gym each day, or working on some property I own in the country, clearing trees and that sort of thing. This kind of exercise can make you stronger physically and mentally.”

Don’t be afraid to cry. “Shedding tears is a body’s way of cleansing itself after a traumatic situation,” Nixon says. “Whenever you need some relief, find an empty office, or go sit in your car, and do what you need to do to lift that weight from your shoulders. Doing that will help you move forward.”

“Most people will experience a traumatic incident maybe five to seven times in their entire life. Meantime, a cop may experience a traumatic incident five to seven times a shift.”

Michael Nixon

![SIDEBAR with headline "4 tips: Be in the know about autism" [TEXT] Children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) wander or go missing at a higher rate than other children—a behavior known as elopement. They may be trying to get away from loud sounds or stimuli, or seeking out places of special interest that pique their curiosities. The National Autism Association (NAA) shares the following tips all first responders should know. • Know the signs: A person with autism may have an impaired sense of danger, and, as such, may wander into water, traffic, or other perils. They may not speak or respond to their name, and may appear deaf. They need time to process questions, may repeat phrases, and may try to run away or hide. And they may rock, pace, spin, or flap their hands. • Know how to search: Act quickly and treat the case as critical since a child with autism may head straight to a source of danger, such as water, traffic, or an abandoned vehicle. First search any nearby body of water, even if the child is thought to fear it. Ask about the child’s likes and dislikes, including potential fears such as search dogs or siren sounds. • Know how to interact: Don’t assume a person with autism will respond to “stop” or other commands or questions. If they’re not in danger, allow space and avoid touching. Get on the child’s level and speak in a reassuring tone, using simple phrases—even if the person is nonverbal. Offering a phone to a nonverbal person to communicate via typing may be helpful. • Know about resources: Beyond agency training, law enforcement officers can find online resources. The National Autism Association offers a downloadable brochure with tips for first responders on its website. Additionally, the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children also offers excellent online resources (visit missingkids.org).](https://amberadvocate.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/AA60-sidebar-autism-1.png)