By Denise Gee Peacock

The 2025 National AMBER Alert and AMBER Alert in Indian Country Symposium, held February 25-26 in Washington, D.C., brought together nearly 200 state and regional AMBER Alert coordinators, missing person clearinghouse managers, Tribal leaders, and public safety officials from across the U.S. and its territories, including American Samoa, Guam, and Puerto Rico.

Presenters and speakers included more than two dozen subject matter experts in missing child investigations and rapid response teams, emergency alerting, law enforcement technology, and Tribal law enforcement. Special guests included four family survivors who shared their powerful stories—and lessons learned.

Also there to address participants was Eileen Garry, Acting Administrator of the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, and U.S. Representative Andy Biggs of Arizona’s 5th Congressional District and co-sponsor of the Ashlynne Mike AMBER Alert in Indian Country Act of 2018.

The annual collaborative learning event is funded through the DOJ’s Office of Justice Programs and administered by the AMBER Alert Training & Technical Assistance Program (AATTAP) and its AMBER Alert in Indian Country (AIIC) initiative, both affiliated with the National Criminal Justice Training Center (NCJTC) of Fox Valley Technical College.

The symposium’s goal is to engage participants in discussing current issues, emerging technology, and best practices for recovering endangered missing and abducted children. Another objective is to improve the process of integration between state, regional, and rural communication plans with federally recognized Tribes from across the nation.

For the second year we enlisted the event management app Whova to help attendees plan their days, share their thoughts, and connect with each other. In keeping with that, we’ll let participants do most of the talking as we share event highlights.

Erika Hock did a great job of presenting the Charlotte Sena case. Her humility shown through, especially when sharing the searching mother’s criticisms [of their alerting process] … and how she’s looking to implement some of the mother’s suggestions.

Ana Flores

This conference is a testament to the power

of collaboration. We’re here to bridge gaps,

share best practices, and innovate.

We’re here to hear the voices of those

who have experienced the unimaginable;

to honor their strength and resilience.

Janell Rasmussen

Never forget the difference you make in a child's

life. Ours is hard work, and sometimes gets us down.

But remember my family’s story. And never lose your

passion for keeping children safe.

Sayeh Rivazfar

AMBER Alert and Ashlynne’s Law

both save lives. Thank you for ensuring

your communities are prepared to

respond to every parent’s worst nightmare.

U.S. Representative Andy Biggs

I will continue to push forward and spread

awareness, particularly about Indian Country,

hoping that one day jurisdiction and sovereignty

will not play a role in the search for a child.

And that every Tribe will have a plan

in place if an AMBER Alert ever

has to be activated.

Jada Breaux

Sayeh [Rivazfar] is an incredible mother, an incredible warrior. Hearing her story was captivating, humbling, and gut-wrenching. As a mother of two young boys, I found her story beyond impactful. It provided a tangible sense of just how urgent it was to return home and continue the work.

Kelsey Commisso

AMBER Alerts: To Activate or Not Activate was my absolute favorite session. Since I’m new to my position, it really made me think!

Whytley Jones

I’d never heard of the ‘Baby in a Box’ case [involving Shannon Dedrick], and the ending surprised me. I loved hearing the investigative lessons learned from it.

Michael Garcia

Pasco County, Florida, Sheriff’s Office Captain Larry Kraus did an excellent job in explaining the application, effectiveness, and obstacles of OSINT. He is super-smart and relatable to those of us who may be tech-challenged.

John Graham

Erika Hock did a great job of presenting the Charlotte Sena case. Her humility shown through, especially when sharing the searching mother’s criticisms [of their alerting process] … and how she’s looking to implement some of the mother’s suggestions.

Ana Flores

This conference is a testament to the power

of collaboration. We’re here to bridge gaps,

share best practices, and innovate.

We’re here to hear the voices of those

who have experienced the unimaginable;

to honor their strength and resilience.

Janell Rasmussen

SYMPOSIUM OVERVIEW

The symposium featured 28 presentations and workshops on relevant and pressing topics within child protection—each meant to deepen attendees’ understanding of current challenges and solutions. Click here to see the full agenda and here to read the speakers’ bios.

FAMILY PERSPECTIVES

- Pamela Foster: Keynote speaker (parental/ AMBER Alert in Indian Country focus)

- Sayeh Rivazfar: Keynote speaker (abduction survivor/law enforcement focus)

- Noelle Hunter: Presenter (international parental child abduction focus)

- Desiree Young: Presenter (parental focus)

INVESTIGATIONS / RESOURCES

- AMBER Alert Coordination: Essential Resources

- Missing Persons Clearinghouse Managers

- National Center for Missing & Exploited Children Updates

- Search Methods in Tribal Communities

- Tribal Response to Missing Children

- U.S. Marshals Service Support for Missing Children

CASE STUDIES

- “Baby in a Box” (Shannon Dedrick / Florida)

- CART Response to Child Sex Trafficking (New Jersey)

- Charlotte Sena Campground Abduction (New York)

- Gila River Indian Community (Arizona)

ALERTING / TECHNOLOGY

- AMBER Alerts: To Activate or Not Activate?

- FirstNet Authority Updates & Resources (Indian Country)

- IPAWS Emergency Communications Updates

- Open-Source Intelligence (OSINT) Analysis

CHILD ABDUCTION RESPONSE TEAMS (CARTs)

- Pasco County, Florida

- State of New Jersey

Knowing that Pamela Foster's daughter, Ashlynne Mike, loved butterflies, AATTAP Administrator/NCJTC Director Janell Rasmussen presented Foster with a meaningful gift. The sterling silver necklace features a butterfly with the name “Ashlynne Mike” intricately cut into its wings. The necklace was crafted by AATTAP-AIIC Project Coordinator Alica Murphy Wildcatt, a member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians.

Sayeh Rivazfar stands with a career shadowbox bequeathed to her by Florida Sheriff's Deputy Randy Mitchell. Mitchell had worked to see justice served after Sayeh was brutally assaulted and her sister, Sara, was murdered by a family friend in 1988. Mitchell was proud of Sayeh's decision to go into law enforcement.

AATTAP Deputy Administrator Jenniffer Price-Lehmann, left, introduces Dr. Noelle Hunter before her powerful presentation on international parental child abduction (IPCA). Hunter's 4-year-old daughter, "Muna," was illegally taken by her non-custodial father to West Africa. She ultimately was able to return home, but only after a "full court press" by Hunter and others to make that happen.

Learning From Survivors: A Top Theme

Sayeh Rivazfar’s life was forever changed on September 22, 1988. That was when her mother’s boyfriend took her, then age 8, and her 6-year-old sister Sara, from their home in Pensacola, Florida, drove them to a remote area, brutally assaulted them, slashed their throats, and left them to die. Sayeh survived; her sister did not.

While living with her father and brother in Rochester, New York, Sayeh chose to join the New York State Police. She has since retired after two decades’ work, but her child protection work continues.

“I decided early on not to let trauma take me down. I use it as fuel to help others.”

Rivazfar displayed a shadow box that belonged to Santa Rosa County (Florida) Sheriff’s Deputy Randy Mitchell. When assigned to her case, the new father was outraged over the pain inflicted on her and her sister. He and Rivazfar kept in touch over the years. “He was proud of my law enforcement career,” she said.

Then, in 2012, shortly before he died of cancer, she received a package from him—his “career in a box,” including his badge and shield, along with a poignant letter. “It means the world to me, as he did.”

'All Abductions Are Local'

On New Year’s Day 2011, Dr. Noelle Hunter’s worst fear was realized: Her ex-husband had illegally taken their 4-year-old daughter to live in his home country of Mali, West Africa.

Thus began the college professor’s quest to have Maayimuna (“Muna”) returned to her—after nearly three years of “full-court press” work.

It’s now her mission to help others navigating the complex mire of international parental child abduction (IPCA).

As an AATTAP/NCJTC Associate, she also helps law enforcement understand how to best respond to IPCA cases. They also should understand this: “All abductions are local. The response a parent gets from that first call for help means everything.”

Pamela Foster: ‘Indian Country Needs AMBER Alert’

Pamela Foster—the mother of Ashlynne Mike, namesake of the Ashlynne Mike AMBER Alert in Indian Country Act of 2018—was introduced to Symposium attendees by U.S. Representative Andy Biggs of Arizona’s 5th Congressional District. Biggs worked with Foster, and Arizona Senator John McCain to ensure passage of “Ashlynne's Law” two years after her 11-year-old daughter’s abduction and murder on the Navajo Nation reservation in 2016.

The Act provides numerous resources to Indian Country to bolster Tribal knowledge, training, technology, and partner collaboration to ensure children who go missing from Native lands can be found quickly and safely.

“Those of you in Tribal law enforcement, if you haven’t already received training, please schedule it as soon as possible,” Foster said. “We need law enforcement on Tribal land to share information with outside agencies so they can quickly apprehend criminals. Every child has the right to feel safe and live life to its fullest, and my fight is based on what I have experienced as a mother and a parent. I don’t ever want what happened to me to happen to another person.”

Foster’s powerful presentation was a gift to all who experienced it. Then she was given a gift—which provided another moving moment.

Read about Pamela's message, and the gift in honor of Ashlynne, here.

From Resources to Technology: More Takeaways

Click each dropdown box below for highlights from top-rated workshops & events.

“We’re good at hunting down fugitives. We’re now putting that toward finding missing children. It’s not something we’re known for. But we want to focus our efforts on kids with the highest likelihood of being victimized, of facing violence.” – Bill Boldin, Senior Inspector/National Missing Child Program Coordinator, U.S. Marshals Service (USMS)

Proven track record: From 2021 to 2024, 61% of missing child cases were resolved within seven days of USMS assistance.

“Mandates are pathways to support.” – Stacie Lick, Captain (Ret.), Gloucester County (New Jersey) Prosecutor’s Office

Having a dedicated, well-trained child abduction response team (CART) is essential to finding a missing child, using all available resources, when every minute counts. But symposium-goers know that building and sustaining a CART are significant obstacles for agencies with slim staffs and budgets.

The CART experts from New Jersey and Florida who shared advice at the symposium have spent nearly two decades overcoming those challenges by thinking creatively and strategically, such as getting buy-in for the expansion of New Jersey's CARTs after the high-profile Autumn Pasquale case in 2012. Or by having a well-thought-through staffing and resource plan, one that can be applied multi-jurisdictionally.

As a result of Captain Stacie Lick’s efforts to compile CART best practices for Gloucester County, New Jersey now mandates that all 21 of its counties have an active CART that follows standardized policies and procedures, and learns from mandatory after-action reporting. In 2008, as Lick was building Gloucester County’s CART, she was greatly inspired by the Pasco County, Florida, Sheriff’s Office (PCSO) Missing Abducted Child (MAC) Team.

Each MAC deploys with a command post with a lead investigator assigned to it. It also has coordinators assigned to these critical tasks: leads management; neighborhood/business canvassing and roadblocks; sex offender canvassing; resources oversight; volunteer search management; search and rescue operations; logistics; public information and media relations; crime scene management; legal representation; analytics; and cybercrimes/technical support. A family liaison and victim advocate will also be on hand to provide valuable assistance.

MODEL MANUALS

Many of the best practices used by the New Jersey and Pasco County, Florida, CARTs can be found in two newly updated, downloadable CART resources—one on implementation and the other on certification—both produced by AATTAP.

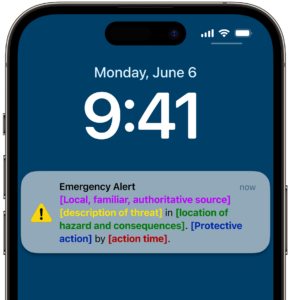

Law enforcement technology consultant Eddie Bertola provided several updates related to the Integrated Public Alert & Warning System (IPAWS) overseen by the Federal Emergency Management System (FEMA).

The IPAWS portal that law enforcement uses to request AMBER Alerts now has a more streamlined interface. And within that is the new Message Design Dashboard (MDD), “an intuitive structure taking message crafting from 15 minutes to five minutes,” Bertola said.

MDD features drop-down menus that provide access to essential information that can be provided in a consistent manner and allow best usage of the 360-character limit within varied templates. It also can check for typos and invalid links and allow for easier message previews and system testing.

In other messaging news, another development is the Missing and Endangered Person/MEP Code, which was discussed in both the IPAWS workshop and updates session hosted by the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC).

Approved in August 2004, the addition of the MEP code to the Emergency Alert System (EAS) will enable law enforcement agencies to more rapidly and effectively issue alerts about missing and endangered persons by covering a wider range of ages and circumstances than AMBER Alerts alone. MEP alerts will utilize the same infrastructure as AMBER Alerts, thus allowing for widespread dissemination through various media channels.

Open Source Intelligence (OSINT) analysis is the leveraging of data from publicly available communication sources such as social media apps, messaging boards, gaming platforms, and the dark web. This research complements more traditional law enforcement databases (criminal databases, LInX, LeadsOnline) and can yield more real-time clues.

Bad actors are increasingly digital obsessed—and inadvertently work against themselves by taking photos and videos with geolocations and time stamps—while leaving other digital breadcrumbs.

OSINT analysts requires continuous training on ever-evolving information-sharing channels. They need to understand how to avoid gleaning intelligence that can be challenged in court (and potentially weaken public trust). All the while they have to battle data overload from the sheer volume of information that needs assessing.

It’s imperative that agencies hire professionals capable of navigating such complexities, Kraus said of intelligence analysts, whom he calls “the unsung heroes of law enforcement.”

FINDING LOST PERSON BEHAVIOR

FINDING LOST PERSON BEHAVIOR

“I can’t believe I didn’t know about the Lost Person Behavior resource,” one attendee said on Whova. Mentioned during Pasco County’s CART workshop, “LPB,” as its known for short, refers to the science- and data-based research of Dr. Robert J. Koester, whose field guide-style book outlines 41 missing persons categories and provides layers of behavior a person in each classification will likely follow.

In his “Genetic Genealogy” presentation, crime scene forensics expert Ed O’Carroll cited several ways to “give people back their names,” adding “crime is more solvable than ever before.”

In his “Genetic Genealogy” presentation, crime scene forensics expert Ed O’Carroll cited several ways to “give people back their names,” adding “crime is more solvable than ever before.”

• Look afield: Re-open a case involving a long-term missing person, or one with unidentified human remains, and let the growing realm of reputable DNA labs help solve a crime once thought unsolvable. “Our labs are overworked, so we need to find more ways to use private ones,” O’Carroll said.

• Be a “genetic witness”: Encourage people on the genealogy sites GEDmatch and AncestryDNA to opt in to giving law enforcement a broader field of DNA samples to consider when trying to pinpoint someone who may have committed a violent crime. “As many of us know, CODIS only gives a hit about half the time we use it.”

• Be a “genetic witness”: Encourage people on the genealogy sites GEDmatch and AncestryDNA to opt in to giving law enforcement a broader field of DNA samples to consider when trying to pinpoint someone who may have committed a violent crime. “As many of us know, CODIS only gives a hit about half the time we use it.”

• “Prevent tomorrow’s victim by solving today’s case today,” O’Carroll said. Know the latest technology, including Rapid DNA, an FBI-approved process that can provide a scientific correlation in as little as 90 minutes.

This was the second year for AATTAP Region 1 Liaison and alerting veteran Joan Collins to teach the popular class designed to help attendees analyze real-world cases of missing children and AMBER Alert requests, noting the key factors within the criteria that determine when an alert is issued; evaluate AMBER Alert effectiveness by comparing case details with activation criteria and assessing factors that influence decision-making; and propose improved response strategies.

Collins’ style is to amiably pepper participants with more than a dozen widely varying missing child scenarios, often throwing daunting updates into the mix. Participants responded using the Poll Everywhere app, which tabulated their responses in real-time on a large viewing screen.

“The alerting sessions instill confidence in new AMBER Alert Coordinators as well as seasoned ones,” Collins said. “The scenarios spark vigorous discussions, and networking with fellow AACs underscores the fact that they all go through the same process, even if criteria may differ.”