By Jody Garlock

Deputy Chief of Police Joshua Sticht has been with the New York State University Police long enough to know the ebbs and flows of student stress levels at the University at Buffalo (UB). The first six weeks of fall semester, and a few weeks toward the end of spring term, one is likely to find students either adjusting to their new environs or finalizing exams and often concerned about their grades. That’s when Sticht and his team are most likely to field missing persons calls, typically from a parent unable to reach their child.

“We get a fair number of missing persons calls, but usually find students reported missing within the first hour,” Sticht said. “It might be something like a student is at a friend’s house and no one has seen them for days.”

But a May 2023 call from a worried mother unable to reach her son before his final exams proved to be far from routine. The wide-ranging case would lead investigators south to Mexico and involve numerous law enforcement authorities, including New York State’s Missing Persons Clearinghouse (NYMPC), the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and the AMBER Alert Training and Technical Assistance Program (AATTAP) of Fox Valley Technical College.

The case’s outcome was a positive one, with the teen swiftly and safely located, thanks in large part to a word all involved in the case mentioned: “Collaboration.” There was collaboration between the parents and UB police; between UB police, the NYMPC, and FBI; and between the NYMPC and AATTAP. Collaboration was also strong between AATTAP and contacts developed through its Southern Border Initiative (SBI), which works to support the seamless operation of AMBER Alert plans in cross-border abduction cases.

“We have access to a lot of technical tools here, but once someone is out of the state, we’re really stuck,” Sticht explained. “Collaborating early and bringing in a number of different resources was key.”

The case also reflects how AMBER Alert programs are used more broadly as a cornerstone tool to locate endangered missing youth. In this case, the missing student was 19—making him too old for an AMBER Alert. But his age, combined with facts uncovered by New York law enforcement, proved he was indeed vulnerable and perhaps in grave danger.

The investigation unfolds

On May 11, a resident adviser—responding to a welfare check prompted by the boy’s mother— discovered the student had not been seen for two days. The adviser promptly reported the student missing to UB police, who in turn visited his dorm room. There they discovered two “red flags”: His cellphone had been left behind (“College students just don’t do that,” Sticht said) and his university-issued ID card— needed to access campus buildings and his meal plan—had not been used in several days.

“This ramped up our concern,” Sticht said. “Sometimes we have situations where everyone is in full-blown panic mode, and we find the person studying in the library. But this was different. No [electronic] devices were hitting the networks. And every tool we would normally use [to locate someone] was hitting a dead end.”

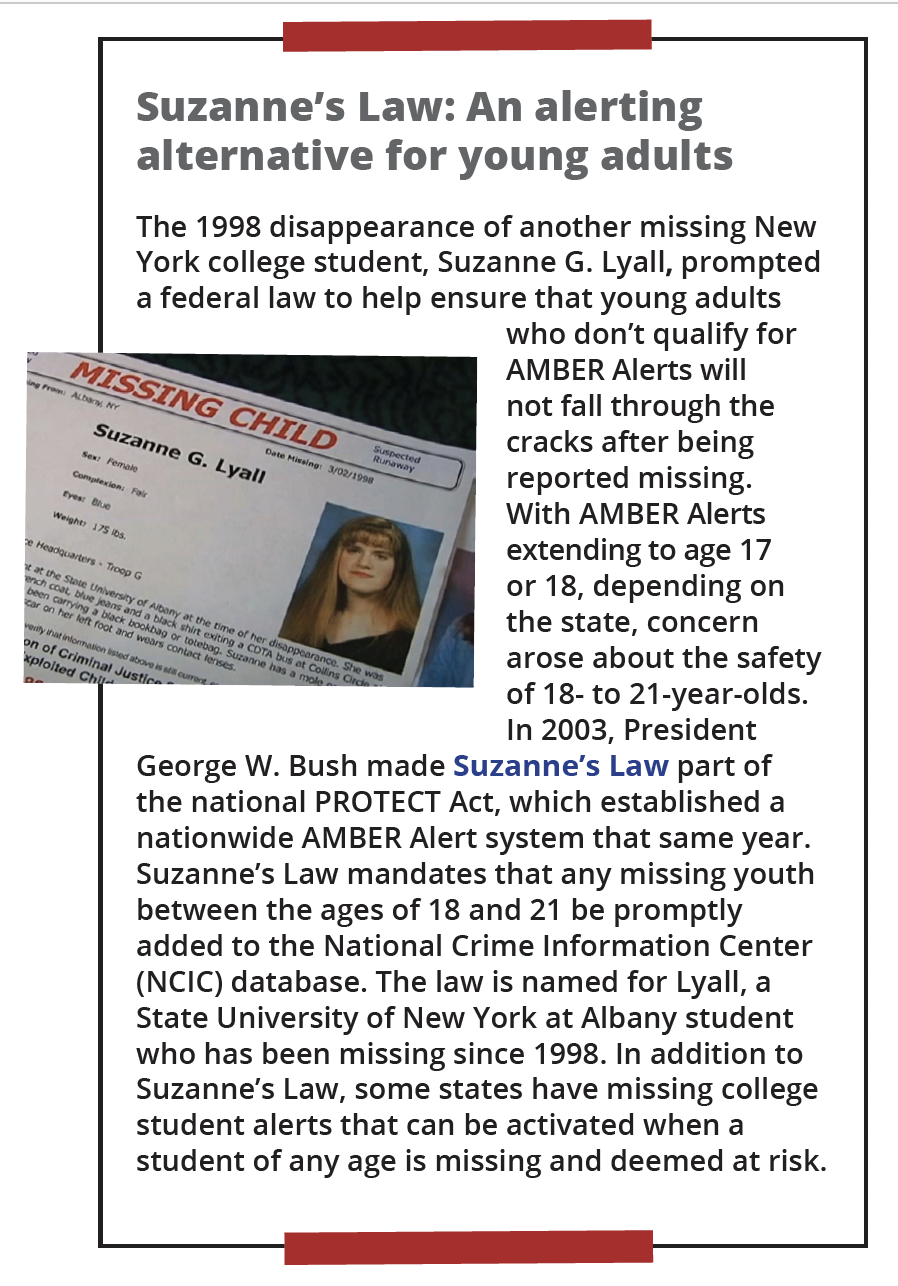

Within hours, UB police added the missing teen to the National Crime Information Center (NCIC) database in accordance with Suzanne’s Law (enacted after another endangered missing New York college student was ineligible for an AMBER Alert; see related sidebar).

Within hours, UB police added the missing teen to the National Crime Information Center (NCIC) database in accordance with Suzanne’s Law (enacted after another endangered missing New York college student was ineligible for an AMBER Alert; see related sidebar).

The following day, New York State’s Missing Persons Clearinghouse (NYMPC) received additional information from the boy’s mother that led them to consider issuing a Missing Vulnerable Adult Alert for him.

The mother had reported to NYMPC that her son was on the autism spectrum and had poor decision-making skills. Online luring seemed a possibility. The parents had learned their son had been communicating via the Discord app with individuals in Mexico and had used PayPal to send someone money.

They also noted that on May 8—the last day their son had used his university meal plan—he had withdrawn funds from his bank account. What’s more, he had recently asked his mother for his passport, explaining he planned to visit Niagara Falls, which straddles the Canadian border.

They also noted that on May 8—the last day their son had used his university meal plan—he had withdrawn funds from his bank account. What’s more, he had recently asked his mother for his passport, explaining he planned to visit Niagara Falls, which straddles the Canadian border.

After a review of his cell phone records showed he had made a 3 a.m. phone call to Delta Airlines, all indications pointed to his attempt to travel to Mexico. Meanwhile, UB officers were able to confirm the student had flown out of Buffalo to Shreveport, Louisiana, giving them “a lucky break” in the case, Sticht said. But with 1,200 miles separating the New York team from the boy’s last known location, collaboration with other law enforcement agencies would need to happen quickly.

Tim Williams, Missing Persons Investigative Supervisor at the NYMPC, contacted the New York State Intelligence Center (SIC) to inquire about getting help from U.S. Border Patrol, and together they learned the youth had flown from Shreveport to Dallas, and on to Mexico City. With confirmation that the teen was no longer in New York—or even the country—a Missing Vulnerable Adult Alert was nixed. Instead, after Williams briefed NYMPC Manager Cindy Neff on what was now a cross-border case, she decided to contact Yesenia “Jesi” Leon-Baron, who coordinates AATTAP’s international and territorial training and outreach, including the Southern Border Initiative.

That proved to be a smart move, Neff said. Leon-Baron had FBI contacts at the U.S. Embassy in Mexico City, and within an hour Leon-Baron was talking with the U.S. Office of Overseas Prosecutorial Development, Assistance and Training (OPDAT). In turn, the OPDAT source was briefing the U.S. State Department’s American Citizen Services group on the case.

Surprisingly swift resolution

On May 13—roughly 48 hours after the teen was reported missing—Mexican authorities located him in Querétaro, about 135 miles north of Mexico City. The youth had begun using a different name and living in an apartment with two people close to his age. Local authorities and the FBI interviewed the teen, who said he was fine. But he wanted to stay in Querétaro. The parents confirmed his identity via photos and spoke with their son.

While the parents are exploring ways to best help their son, those involved in the search for him are proud of how quickly they were able to locate him in another country—and how relieved they were to know he was found unharmed.

Neff credits Leon-Baron for accelerating the search due to her connections in Mexico: “Once Jesi reached out, they got right on it.”

The case represents “the very essence” of AATTAP’s mission to build relationships and collaborate, Leon-Baron said. “The success of this investigation is due to the partnerships built with AMBER Alert Coordinators in the U.S., and Southern Border Initiative relationships established in Mexico,” she said.

Having solid relationships ahead of time was crucial, Leon-Baron says. “It’s being the bridge, if you will, to pass it on. Without that, it would have prolonged the opportunity to recover the teen quickly.”

Back on the UB campus, Sticht is pleased with the work of his officers, who remained the point of contact for the parents even after the case left his team’s jurisdiction. “Collaboration is really what got this done,” he said.

Noticing their son was becoming more secretive, distracted, and easily agitated, the couple investigated the game’s communications log for clues to his behavioral changes. They were distraught to find that he was conversing with a gamer named “Hunter Fox” who identified as a “furry” (someone who enjoys dressing up as a furry animal).As they combed through the text-like interactions, they saw the conversation had increasingly become sexualized in tone. But because such language might be flagged, and hinder the gamers’ access to Roblox, “Hunter” discussed using other digital platforms to continue communication.

Noticing their son was becoming more secretive, distracted, and easily agitated, the couple investigated the game’s communications log for clues to his behavioral changes. They were distraught to find that he was conversing with a gamer named “Hunter Fox” who identified as a “furry” (someone who enjoys dressing up as a furry animal).As they combed through the text-like interactions, they saw the conversation had increasingly become sexualized in tone. But because such language might be flagged, and hinder the gamers’ access to Roblox, “Hunter” discussed using other digital platforms to continue communication.

Six minutes after a 5-year-old autistic girl was reported missing, an officer just two weeks into his first assignment rapidly responded to a law enforcement alert, identifying and safely recovering the child. Amazingly, he had noticed the child just moments before standing on the porch of a neighbor’s home when heading out for his patrol shift. The officer’s attentiveness to call activity and his situational awareness were central to his swift and targeted response to the incident.

Six minutes after a 5-year-old autistic girl was reported missing, an officer just two weeks into his first assignment rapidly responded to a law enforcement alert, identifying and safely recovering the child. Amazingly, he had noticed the child just moments before standing on the porch of a neighbor’s home when heading out for his patrol shift. The officer’s attentiveness to call activity and his situational awareness were central to his swift and targeted response to the incident.

A frantic search for a nine-year-old deaf girl took place during a tabletop exercise for the York County Child Abduction Response Effort (CARE) Team in York, Pennsylvania, on September 17, 2020. The drill used realistic documents and involved simulated neighborhood canvassing, checking Megan’s Law offenders, analyzing video surveillance, and utilizing forensic searches and cell phone tower data.

A frantic search for a nine-year-old deaf girl took place during a tabletop exercise for the York County Child Abduction Response Effort (CARE) Team in York, Pennsylvania, on September 17, 2020. The drill used realistic documents and involved simulated neighborhood canvassing, checking Megan’s Law offenders, analyzing video surveillance, and utilizing forensic searches and cell phone tower data.

“Initially this case was treated as a missing persons case,” said HPD Homicide Lieutenant Zachary Becker.” Jeremiah’s mother did not initially consider him at risk because he was in the care of a trusted family member who was late returning home.”

“Initially this case was treated as a missing persons case,” said HPD Homicide Lieutenant Zachary Becker.” Jeremiah’s mother did not initially consider him at risk because he was in the care of a trusted family member who was late returning home.”

November 20, 2017*: An AMBER Alert for a missing 12-year-old girl has been canceled after she and her alleged abductor were found safe in Des Moines following a traffic stop on I-235.

November 20, 2017*: An AMBER Alert for a missing 12-year-old girl has been canceled after she and her alleged abductor were found safe in Des Moines following a traffic stop on I-235.

Charlmaine Wilson and Omar Parrine were walking along the street when they received the AMBER Alert on their cell phones; they spotted a toddler matching the alert description in his car seat on a sidewalk next to a porch.

Charlmaine Wilson and Omar Parrine were walking along the street when they received the AMBER Alert on their cell phones; they spotted a toddler matching the alert description in his car seat on a sidewalk next to a porch.