By Denise Gee Peacock

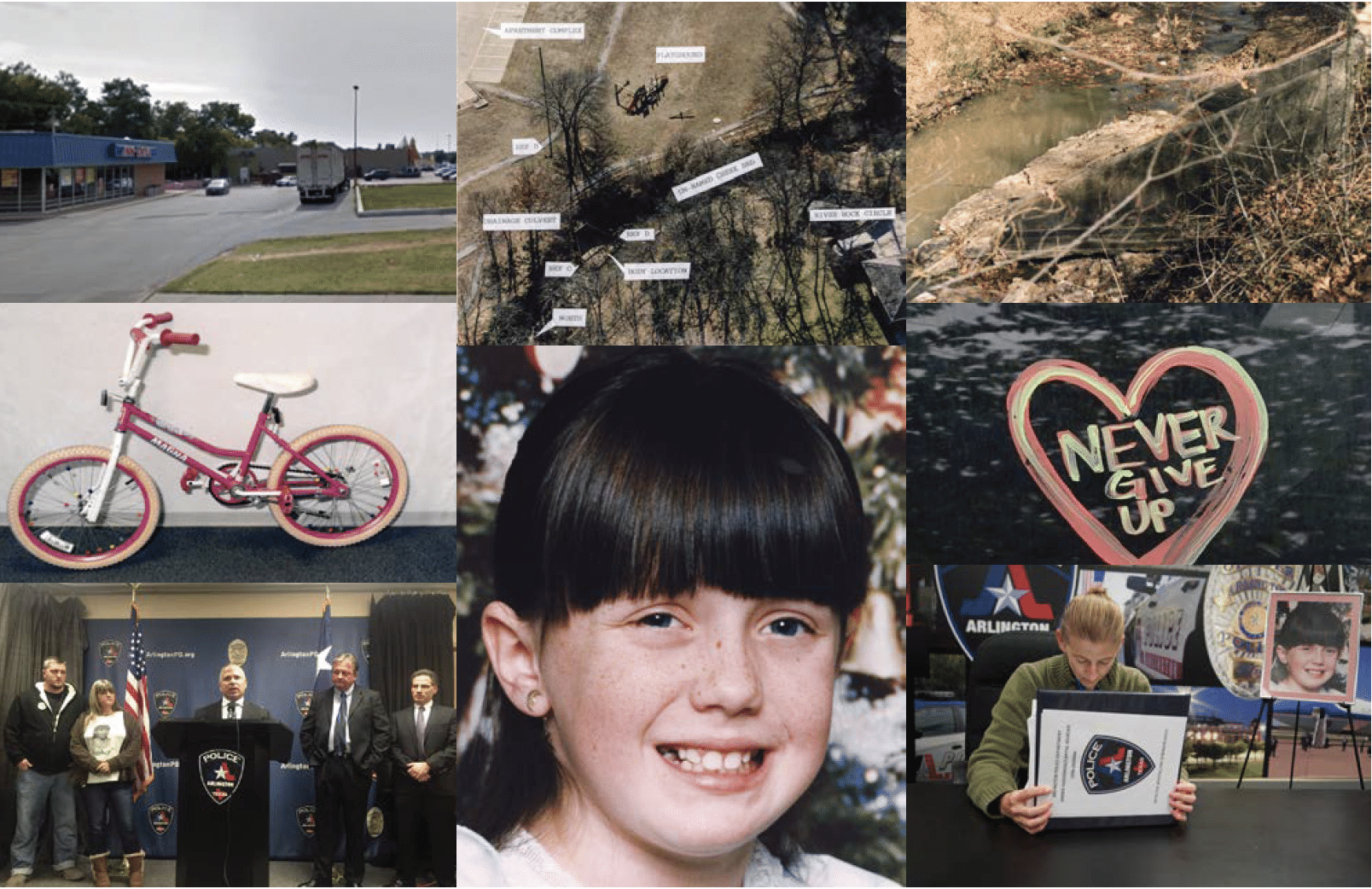

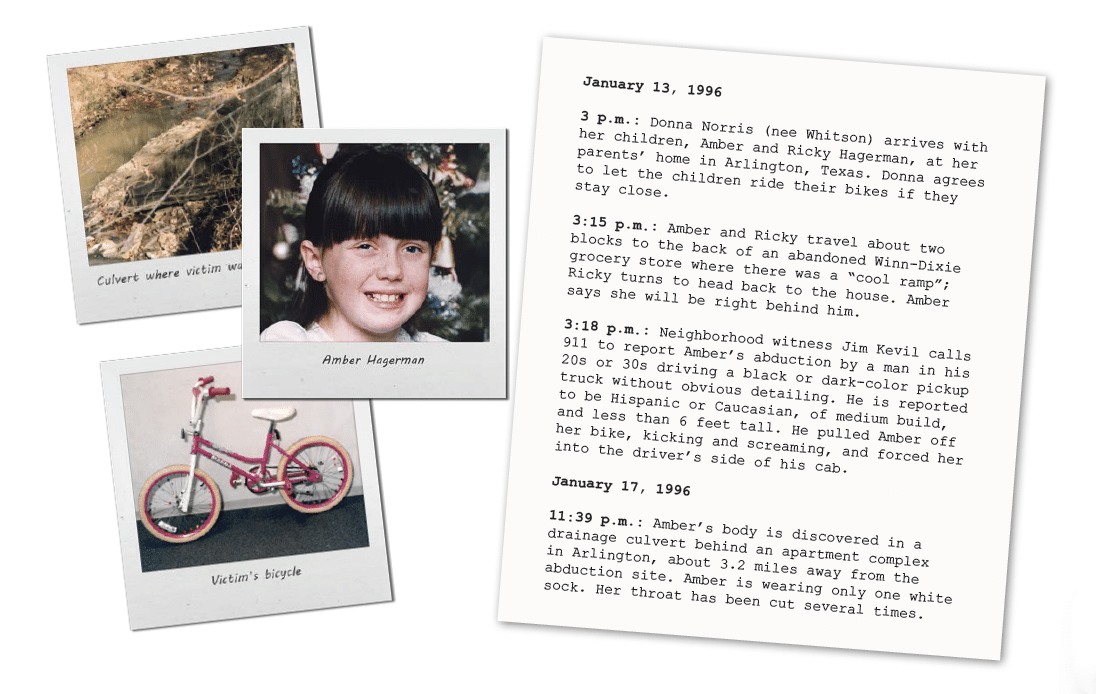

As the 30th anniversary of Amber Hagerman’s murder approaches, the search for her killer continues. Mark Simpson, the case’s original investigative supervisor at the Arlington Police Department (APD) from 1996 to 2007, reflects on a crime that transformed policing.

“We realized ... we didn’t have a major case response plan,” he recalls. The tragedy forced advancements, most notably the AMBER Alert system, but for Simpson, the goal remains: “to see the case solved.”

Today, that mission falls to APD Detective Krystalynne Robinson. She keeps Amber’s portrait near her desk as a daily reminder. Despite thousands of leads and decades of work, the case is far from cold; tips still arrive weekly. Robinson is now vetting labs for advanced DNA testing, driven by the same unwavering goal: “to get justice.”

Former Investigation Supervisor Reflects on Early Days of Case—And Lessons for Today

Texan Mark Simpson was the Arlington Police Department’s Investigative Supervisor for the Amber Hagerman case from the time of her abduction and murder in 1996 until 2007, when he retired after a 32-year career with the APD. We recently caught up with him to discuss his recollections of the case— and what he wants more than anything: “to see the case solved and justice served.”

As we approach the 30th anniversary of the Amber Hagerman abduction and murder, what goes through your mind?

The likelihood that whoever committed the crime may still be out there troubles me. But I also look at everything that resulted from Amber’s death—the advancements law enforcement has made, not only in training but also investigative tactics, and our ability to respond to child abductions, including the AMBER Alert system—that we didn’t have before. It’s horrible that it took this little girl’s death to do that, but at least her death was not in vain.

What were some advancements within the Arlington Police Department?

We realized pretty quickly into Amber’s investigation that we didn’t have a major case response plan. For a situation requiring immediate, extensive deployment of personnel, who would we deploy? How long would we deploy them? In a major deployment, you can push people 18 hours, 20 hours, sometimes more, but then they start to make mistakes. And afterward, if you haven’t accomplished what you set out to do, what is the follow-up plan? There’s got to be a transition into another group of detectives who can keep the investigation moving. We had a lot to learn—and rapidly.

Was this a precursor to a child abduction response team (CART)?

I wish we’d had the tremendous forethought to create a CART back then, but our work was more reactionary. Later, when I began teaching for the National Criminal Justice Training Center (NCJTC) of Fox Valley Technical College, the emphasis on CART creation was bringing in people from different disciplines, from different jurisdictions, people who each brought something different to the table. But at the time, our team was learning as we were going.

How did you keep up with all the investigative leads?

Leads management was a huge learning curve. Unless you’ve ever been hit with a case like the Hagerman one, it’s hard to describe the amount of intelligence that comes in very quickly. We investigated more than 7,000 leads during my tenure. And a lot of that information was time sensitive. To manage it, we needed to learn how to get the information into a searchable database, how to collate it, how to determine what needed to be dealt with immediately, and how to quickly get the information to the people who could use it. We also had endless rows of three-ring binders with hard copies of investigative reports to organize. That was extremely labor- and resource-intensive, but we didn’t want to be in a situation where we might be reinvestigating the same lead over and over.

How has Amber’s case weighed on you?

Well, justice has yet to be served to the killer. That bothers me. And what was done to Amber is not the kind of thing that you go into a bar and have a few drinks and brag to your buddies about. It’s something you either take to your grave or wind up letting slip to someone very close to you. So I can only hope that someone will one day talk, and that will lead to a reckoning for Amber’s death. Someone needs to be held to account.

And as for the investigation?

I know with certainty that we did everything that we could do to push the case forward, so I have no regrets. I was given every resource I asked for, and even got to handpick the people who investigated the case. They were considered some of the brightest minds around.

Tell us about the investigative task force.

When Amber was first abducted, the city devoted 45 detectives and four sergeants to her case alone. I was one of those four sergeants. Within about 30 days, we pared it back to 15 detectives and one sergeant, with that sergeant being me. I chose people who were very good at their jobs—at interviewing, at interrogations, who had strong attention to detail, who had a deep sense of integrity. We were a standalone task force for about 18 months until our time came to a close, which was hard. The people on that task force, when they left, they left in tears. These were grown men who did not want to quit. But after the task force disbanded and I went back to working homicide, the case followed our team there and we kept it alive.

Did that spur your decision to open a cold case unit?

It was one of the reasons. We wanted to stay focused on Amber’s case as long as we could. For context, we decided a cold case would be one that had gone 120 days without a viable lead. But interestingly, during my time with the Arlington Police Department, Amber’s case never went 120 days without actionable intelligence. So technically it never went cold.

What was the most challenging aspect of working the case?

Keeping an aggressive investigative stance. Time is your enemy during child abduction investigations, since the longer they go, the more likely that people’s memories will fade, and crime scenes yet to be identified will be corrupted or disappear. You’ve got to keep moving very deliberately, with as much speed as possible, and leave no stone unturned. But you also have to be mindful not to investigate so many things at one time that you wind up not doing any of the tasks well. My job was to make sure that the 15 detectives on our task force had the resources they needed to do the job, that they had the freedom to make good decisions, and I could help them keep extraneous baloney at bay. For the most part, that was allowed to happen. The goal was to keep everyone from feeling overwhelmed. That’s when you lose track of your priorities. How did you try to boost morale? One way was in our command post. I kept a timeline of our work that ran all the way around the room and continued yet again. The reason I did so was twofold. One reason was for easy reference. But the other was to have a visual representation of what we were doing as a team. Leads were coming in hand over fist, and I wanted them to see what they were getting done—not only to develop new strategies from what everyone was finding, but also to underscore that while we didn’t have an arrest, we were still making progress. Tell us about your relationship with Amber’s family. Relationships in such cases can be complex, but we all became pretty close. The family knew they could call us 24/7/365, which was important. Most people do better when they approach something from a position of knowledge, so we made sure lines of communication stayed open. We had several formalized briefings with them, but over time we slowed that down simply because there wasn’t much new to share. It was about that time when I could see Donna losing patience with us. She appeared on television and said some not-very-nice things about me. But I realized it wasn’t personal. She was just frustrated because she didn’t know exactly what was happening.

How did the situation resolve?

Our victim assistance coordinator, Derrelynn Perryman, told me that Donna wanted to visit the command post. I said, ‘No. We have sensitive information in there; nothing good could come from that.’ Well, Derrelynn worked on me for about a week until I relented. I said, ‘OK, Donna can come up, but here’s a list of things she can’t do in there. She can’t be left alone, or take any pictures, that kind of thing.’ So Donna comes up to the post, and all the detectives clear out except for me. She sits down and looks around for what seemed like an hour but was probably only 10 minutes. She then gets up and walks out. And I thought, well, that wasn’t so bad. A few days later Derrelynn returns and says, ‘Donna wants to come back to the command post.’ So again, I say no, but again I get talked into it. This time Donna comes in with a paper sack. And in that sack is a framed photo of Amber. It was a Christmas picture, one that wound up being used on many of Amber’s flyers. She wanted us to hang Amber’s picture on the wall, which we did. She also gave us a Native American Kokopelli figurine. She wanted that in there with us too for some reason. Then she took a piece of paper and a Sharpie and wrote ‘Amber’s Room’ on it. She wanted that on the door of the command post. So I had an actual sign made that read “Amber’s Room’—one that could replace ‘Conference Room 3.’ And that was the beginning of the change between the Arlington Police Department and Donna. She just needed to see we were doing something. She wasn’t sure exactly what we were doing, but she could see it was progress. She also felt a personal connection to the space. It dawned on me then that you have to think outside the box in your work with families, especially if you feel like you’re losing touch with them. I’d been too focused on what you might call less holistic things until Derrelynn, and Donna, helped me see that.

What do you remember about the public’s reaction to the case?

When I think about when Amber was abducted, I don’t know exactly how to describe it, but the city and the news media was like an animal that had to be fed. People were just absolutely incensed that this type of crime could happen in our community.

What do you think most resonated with people?

Looking back on it, one difference was the media’s use of video. WFAA Channel 8 had been shooting a documentary about Amber and her family for a story about families living on, and off, welfare, and that footage really struck a chord with people. People felt like they knew Amber. We didn’t just have a photograph of her, but we had moments with Amber—her riding her bicycle, her doing homework, her playing with her little brother, Ricky. That video really brought that little girl to life, and made so many people want to do something to help.

Tell us about your relationship with the media during that time.

Historically, law enforcement has tried to keep the media at arm’s length. But my philosophy was to give the media anything and everything if it didn’t negatively impact our investigation. The more they knew, the better off we could be with our police work, especially since the media helps us connect with the public. If we’d chosen to shut out the media, they would have hunted for information on their own that may not have been accurate.

What do you think about how technology has changed in the past 30 years?

Unfortunately, our work occurred during a very different time. We didn’t have the ability to geolocate cellphones in a certain area or have license plate readers check tags near a specific location. There were no doorbell cameras. Back then there was only one security camera at a convenience store across the street from where Amber was abducted—and the camera wasn’t outside, but inside, pointed down on a register, so they could watch themselves get robbed. The electronic fingerprints people leave behind now are huge. But there’s one skill that need not get lost among the technological advances. Investigators should maintain the ability to simply talk with people. That also yields important results.

What did you know about DNA evidence at the time of Amber’s investigation?

We knew enough about it to hang onto whatever evidence we could to await future advances in the technology, which was in its infancy at the time. There are so many options for DNA testing now, so many potential strategies that we didn’t have back then. As time goes on, that will do nothing but expand.

What advice do you give law enforcement about improving responses to missing child cases?

What’s important is to have a plan. Know what you’re going to do if this type of case happens so that you can move rapidly and deliberately to get the investigation off the ground. Also, get trained. Nobody has any better instructors or better materials or message than the NCJTC and AMBER Alert Training & Technical Assistance Program. It’s no good trying to figure things out in a parking lot somewhere while your suspect is fleeing somewhere with your victim. Lastly, stay current on your resources—personnel, equipment, specialized assistance. Because over time, resources will change. You might have people with a particular investigative strength today, but in six months, they may have moved on. Who will replace them? That’s a planning reality that shouldn’t be overlooked.

Lead Investigator Now Assigned to Hagerman Case Discusses Hopes for DNA Testing—and Goal of Solving the Crime

Arlington Police Department Homicide Detective Krystallyne Robinson has been the lead detective on the Amber Hagerman case since summer 2023. We recently had the chance to ask her a few questions.

What’s your perspective on the 30th anniversary of Amber’s case?

It’s a huge milestone—one that gives us the opportunity to keep the focus on Amber while encouraging the public to share what they may know about the case.

On the 25th anniversary the Arlington PD discussed the possibility of DNA testing being used for the investigation. What’s the latest on that?

Since the amount of physical evidence that we have is very limited, I’m in the process of vetting labs to make sure they can do what we need them to without consuming the entire sample. Given the advancements in technology—that are just continuing to advance—I’m hopeful about the work the labs can do.

What else should we know about the case?

I want people to know this case isn’t on the backburner for the Arlington Police Department, or for me. It’s important for our department to solve this crime.

What drives you forward to do that?

I keep a framed portrait of Amber in my office. It’s near my desk, and it’s the first thing I look at every day. That means there’s literally not a day that goes by that I’m at work and I don’t think about her.

What’s your investigative approach, given the years that have passed?

It’s important that I continually have a fresh approach to the case, and keep an open mind. I teach a lot at the academy, and tell the recruits, you have to be self-consciously aware of the things that you’re doing and in the way you approach your investigations. That’s true for any case, but especially Amber’s. We have to just keep digging—digging into the leads and the evidence.

How often do you get leads on the case?

We get phone calls, emails, and letters about the case at least weekly. I know I don’t go a month without receiving an email or phone call related to it.

What would you say to Amber’s family?

As Amber’s mother knows, I’ve put a lot of work into this case—going through every report and previous detectives’ narratives. Our goal is always to get justice, and that’s what we’re aiming for. We also never want Amber’s name to be forgotten.