By Rebecca Sherman

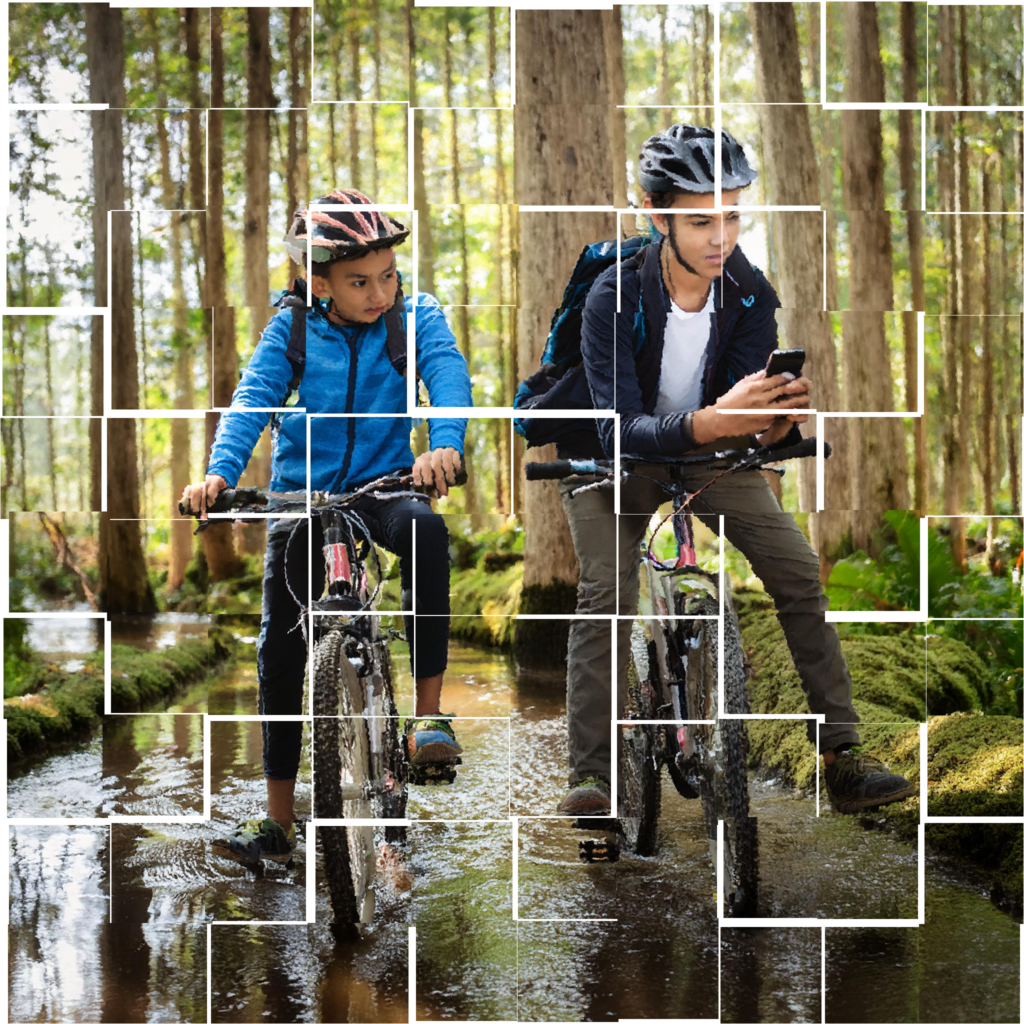

David Boots, Battalion Chief of the Denton, Texas, Fire Department, was at home listening to radio communications when the call went out. It was 8:30 p.m. on June 5, 2024, and the sun was beginning to set. Two teenage boys on bikes were stranded deep inside Denton’s Greenbelt Corridor, a 20-mile, heavily forested nature trail connecting the Ray Roberts Dam with the headwaters of Lake Lewisville.

Chief Boots felt a knot in his stomach. He knew the area well; the department had rescued hikers who had become lost on the trail before, but this time was different. Storms earlier in the week had created treacherous flooding conditions that forced the closure of the Greenbelt.

Getting the teens out in the dark would be difficult and risky, not only for them, but also his rescue teams. Worse still was the news that high winds and torrential rains would soon be barreling in from Oklahoma. “A flooded greenbelt is not a good place to be during a storm,” Boots says.

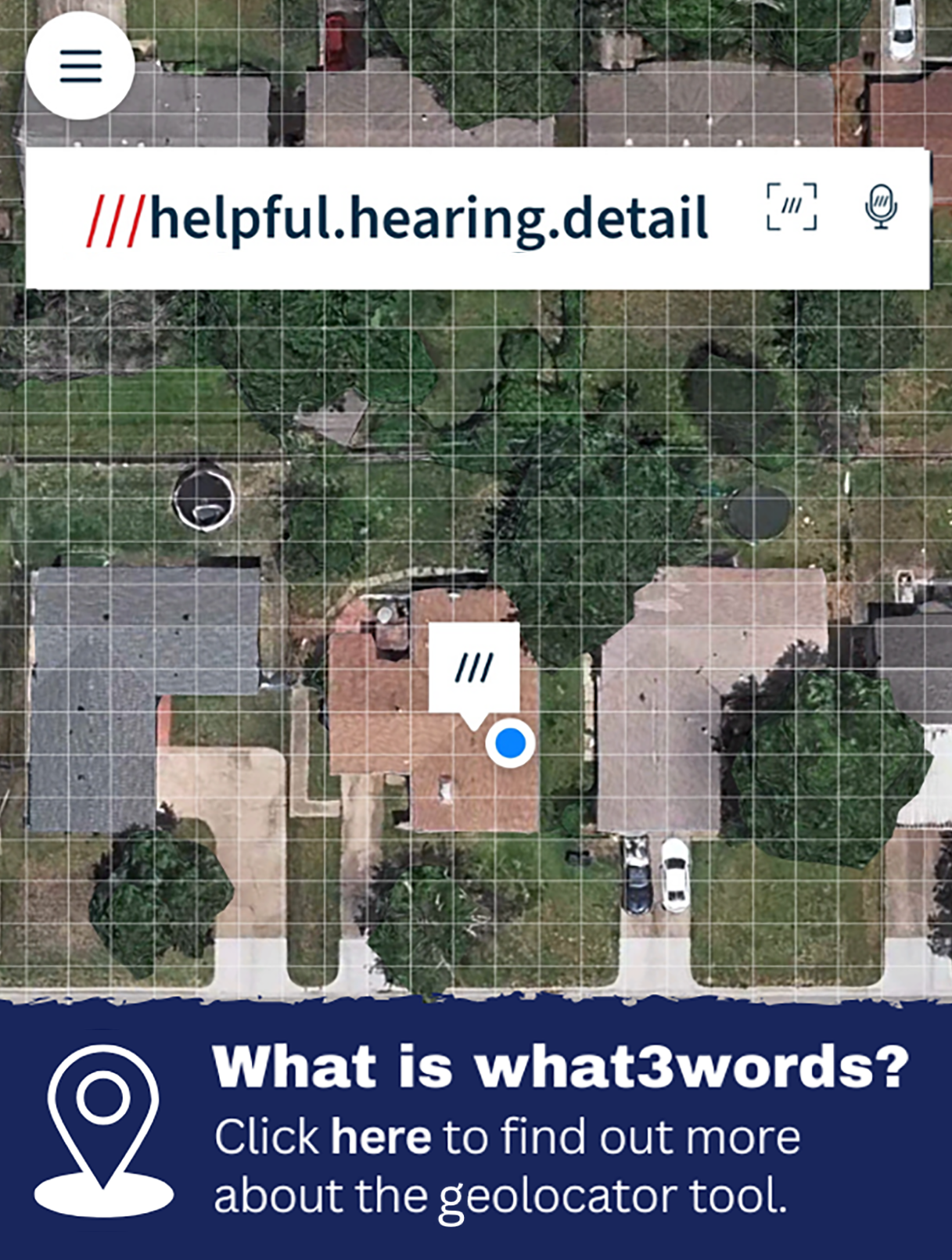

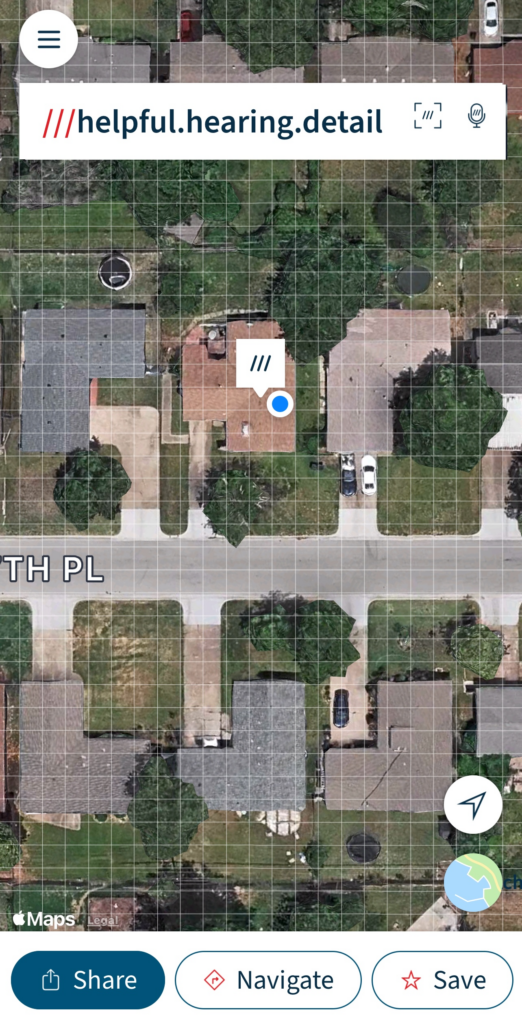

Thankfully one of the teens had a cell phone with him. And the Denton Police Department had access to what3words, a revolutionary new geolocation tool.

The boys’ day had begun well enough, with sunny skies accompanying them on their morning ride to the lake. But after wheeling onto the Greenbelt trail, bypassing closure barriers, they found themselves in dire straits. They had lost their bearings trying to navigate around impassable, and at times impossible to see, pathways to safety. They had no real sense of where they had meandered, or the danger they were in, and needed to be located and brought to safety quickly. Their lives were in danger.

“They got down into swampy water—deep at times—and muddy, with logs covering the trails,” Boots says. The boys had been there for hours. “One of their cell phones went dead,” Boots continues. “When the sun went down, they were well into the Greenbelt and surrounded by water. They knew they were in trouble.”

When the boys called 911, the Denton Police Department Dispatch Center enlisted what3words technology to immediately pinpoint their precise location—as well as the best route to find them. That data was then forwarded to rescue teams.

In the past, the Denton Police Department relied solely on triangulated pings from nearby cell phone towers to get a general idea of where to find missing individuals when mobile devices were involved. And while they could also request helicopter assistance, such resources take time to deploy. Thus, the location data provided by what3words has proven to be invaluable, says Suzanne Kaletta, Assistant Director of Public Communications for the City of Denton. The app’s accuracy has been “a game-changer” since they began using it in 2022, Kaletta says. It has shaved hours from searches involving difficult terrain.

Harrowing Rescue Mission

Racing against time, Boots led more than 20 rescuers who were deployed to find the teens. “We put an ATV in at the halfway point between the lakes, but it couldn’t get to them,” he says. “Another team in an inflatable boat had to paddle the creek upstream to try to get close enough, but debris blocked the way.” The team abandoned the boat and set out on foot, in the dark and through deep, snake-infested waters.

In the summer heat, the rescuers were “soaked to the bone and sweating so much they had trouble holding onto their phones for navigation,” Boots recalls. A drone crew attempted to guide their way, but the forest’s dense tree canopy below made it difficult to spot them.

Rescuers reached the teens at around 11:25 p.m., some three hours after their call to 911. They were hot, wet, tired, and scared—and their ordeal was far from over. A journey with rescuers leading the way back to the boat through swampy floodwaters and nighttime conditions still lay ahead. So did the storm’s approach from the north.

Everyone was on edge as they did the mental countdown of when it would hit. “We knew we had an hour; then just 30 minutes,” Boots says. “We finally got them out with 15 minutes to spare. It was unnervingly close.”

And this much is certain: Without the geolocation assistance from what3words—coupled with the tenacity and skill of the North Texas emergency responders—the boys may not have made it out of the woods.

Who created it?

Who created it?

Share your feelings with a trusted friend or professional.

Share your feelings with a trusted friend or professional.