Shown at the Summer 2024 needs assessment meeting in Guam (from left): AATTAP Associate Eddie Bertola; AATTAP Project Coordinator Derek VanLuchene; Guam Homeland Security Director Esther Aguigui; Governor Lourdes “Lou” Aflague Leon Guerrero; Lieutenant Governor Josh Tenorio; AATTAP Administrator Janell Rasmussen; AATTAP Project Coordinator Yesenia “Jesi” Leon-Baron; and AATTAP Deputy Administrator Byron Fassett.

Shown at AATTAP's 2024 Northern Border Initiative focus group meeting in Bonners Ferry, Idaho (from left): Yesenia “Jesi” Leon Baron, AATTAP Project Manager for territorial/international & Northern/Southern Border Initiatives; Nicole Stone, Mukilteo Police Department; Kara Kelley, Idaho State Police; Clara Dunnington, Kootenai Tribe of Idaho Council; Traci Whelan, U.S. Attorney’s Office; Janelle Ball, Royal Canadian Mounted Police; Autumn Diller, Kootenai Tribe of Idaho Police Department; Angela Cooper, Kootenai Tribe of Idaho Council; Carri Gordon, Washington State Patrol / AATTAP Region 5 Liaison; Heiko Arshat, Chief of Kootenai Tribe of Idaho Police Department; Ruben Ortiz, AATTAP Associate; David Messick and Micheal Christensen with Customs and Border Patrol; Byron Fassett, AATTAP Program Manager; and Melissa Stroh with the Idaho State Police.

By Denise Gee Peacock

The United States’ 14 territories—three in the Caribbean, 11 in the Pacific—play a key role in ensuring our collective national security. In turn, the U.S. ensures each homeland has the security it needs to protect its own—especially its children. That’s because the need for AMBER Alerts resonates in every language.

In the past 30 years, AMBER Alert programs have helped law enforcement safely recover 1,200 missing children. Those successes—and lessons learned from not having plans and resources in place to quickly mobilize when a child goes missing—have prompted other countries to seek guidance from the AMBER Alert Training & Technical Assistance Program (AATTAP).

As a U.S. Department of Justice initiative, the AATTAP—part of the National Criminal Justice Training Center of Fox Valley Technical College—provides free training and technical assistance to U.S. territories, Indian Country, and other countries with Department of Justice (DOJ) funding. Trainings improve law enforcement’s response to cases of endangered missing and abducted children. They also address endangerment dynamics that often are not well understood: high-risk victims, children in crisis, and the commercial sexual exploitation of youth.

Since all U.S. territories are islands, careful consideration of weather is always in play, with hurricanes and typhoons threatening both travel and infrastructure.

AATTAP’s work with each territory includes first conducting high-level needs assessment meetings to learn and understand the important considerations unique to each territory’s cultural, geographic, and technological needs and challenges—to ensure these dynamics are addressed in training and resource efforts. AATTAP’s Child Abduction Response Team (CART) training is also delivered to key partners who will be part of their comprehensive response.

“Each territory’s capabilities and needs can be very different, so we spend the bulk of our time initially listening and learning about the issues they face,” says AATTAP Administrator Janell Rasmussen. “Puerto Rico, for instance, has an AMBER Alert Coordinator and AMBER Alert system in operation. But that’s currently not the case in American Samoa, Guam, or the U.S. Virgin Islands. They’re all at very different places in terms of how they’re responding to cases involving missing children.

“Geographically some of the islands are closer to other countries than they are to us, so these issues have to be considered before we prepare training plans for them,” Rasmussen explains. “Our work has to be developed to address the specific problems they face—whether it’s child sex trafficking or a lack of resources, such as high-speed Internet access.”

Many territories, for instance, do not have access to Wireless Emergency Alerts (WEAs) or the Internet

Public Alert & Warning System (IPAWS). They also lack road signs for public alerting. Additionally, “their children are often taken to a different country, which adds a whole new layer of complexity for collaboration and contact expectations,” Rasmussen explains.

Knowing this, AATTAP leaders and subject matter experts have flown tens of thousands of miles to ensure U.S. territories’ needs can be met. “It’s important they know we offer the same level of training and technical assistance as we do in the States.”

Here are some of the regions where AATTAP partnerships are helping save lives.

American Samoa, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands

From the U.S. mainland, travel to American Samoa, Guam, or the Northern Mariana Islands in the south-central Pacific Ocean requires nearly 24 hours of flying time. American Samoa, for instance—the only inhabited territory south of the Equator—is 2,200 miles from Hawaii to the northeast, and 1,600 miles from New Zealand to the southwest.

For nearly two years, the federal government has been working to uphold National Defense Authorization Act provisions that ensure U.S. territories have the training and technical assistance needed to protect their citizens and children. This includes challenges related to integrating and facilitating AMBER Alert programs.

In February of this year, the team conducted two days of needs-assessment meetings in Pago Pago, American Samoa. Then in July, the team visited Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands to do the same.

As is the case on the U.S. mainland, each needs-assessment meeting involves facilitated discussions about law enforcement procedures, the territory’s needs for fully and quickly investigating missing child incidents, their emergency messaging capabilities, and ultimately what AATTAP training and technical assistance they would like to have.

Reception to the visits was warm and enthusiastic. Often present were U.S. congressional delegates, local and federal law enforcement and telecommunicators, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) dedicated to child protection.

“Our partners are appreciative that we’re willing to go to great lengths to work with them where they live,” says AATTAP Project Coordinator Yesenia “Jesi” Leon-Baron, who manages territorial, international, and Southern/Northern Border Initiatives. “Doing so helps us see what their challenges are in safely recovering endangered and missing children.”

This support is a lifeline to the islands. As Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI) Department of Public Safety Commissioner Anthony Macaranas told the Saipan Tribune, “One of our biggest challenges is that we’re far away from the United States mainland.” Thus, creating or strengthening AMBER Alert plans will help the CNMI build relationships with key members of law enforcement “and help us progressively move forward,” he said.

One case in the Northern Marianas that people would like to see resolved involves missing elementary-school-age sisters Maleina and Faloma Q. Luhk, who mysteriously disappeared while waiting for a school bus near their home in May 2011.

“All of these things we’re getting [from the AATTAP and others] are to prepare us, and the long-term plan is to finally sit down and come up with a strategic plan” on implementing AMBER Alerts, Macaranas said. “It involves a lot of manpower, data, and of course funding … but in the end, we’re going to have this program here.”

Trafficking “is one of the greatest crimes imaginable,” said High Chief Uifa’atali Aumua Amata Coleman Radewagen of American Samoa. To address that, James Moylan of Guam co-sponsored the Combating Human-Trafficking of Innocent Lives Daily (C.H.I.L.D.) Act of 2023, which raises convicted child traffickers’ mandatory minimum jail time from 15 to 25 years.

“Before we left American Samoa, the Governor’s Office presented each of us with a framed ‘warrior’s weapon’—calling us warriors for the missing and abducted children in the territory,” Leon-Baron says.

Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico is the only U.S. territory with an AMBER Alert plan and program coordinator fully in place at the time of this reporting. Their ongoing goal is to continually refine their existing plan and provide a coordinated and sustainable law enforcement response.

AATTAP has been involved in ongoing assistance with Puerto Rico since holding the first in-person training session there in January 2023. Team members delivered the Child Abduction Response Team (CART) training, along with Rescue, Recovery, and Reunification field-training exercises for CART members and other law enforcement in Puerto Rico.

In May 2024, the AATTAP team returned for a needs assessment visit to discuss Puerto Rico’s ongoing challenges, emerging trends, and the training and technical assistance needed to bolster response readiness.

Puerto Rico’s law enforcement leaders intend to continue CART training, Leon-Baron says. They also plan to participate in such courses as AMBER Alert Activation Best Practices (AAABP), Initial Response Strategies & Tactics When Responding to Missing Children Incidents (IRST), and Search and Canvass Operations in Child Abductions (SCOCA).

Southern Border Initiative (Mexico) and Northern Border Initiative (Canada)

AATTAP’s well-established Southern Border Initiative (SBI) is focused on building preparedness for effective response to cases of endangered missing and abducted children in Mexico and the U.S. through cross-border collaboration and planning. Meetings AATTAP has held with federal and state partners in the last two years have underscored the impact of this type of collaboration.

The most recent meeting—held August 1 in Chula Vista, California (across the border from Tijuana, Mexico)—drew more than 100 law enforcement and NGO members who rely on cross-border collaboration to bring missing children safely home. AATTAP piloted a full-day version of its Cross-Border Abduction training, with some participants leaving their homes at 2 a.m. to attend, Leon-Baron says.

AATTAP Associate David Camacho recalled the impact of the event: “We were thankful to have them all there; they had amazing questions, and we reviewed them carefully.”

One conversation “was tough to even consider,” Leon-Baron says. “Some shared with us that in Tijuana, there’s a movement to allow a child of age 9 to consent to sex.”

This is one of many cultural issues that need to be addressed, Leon-Baron says. “We know their laws and judicial processes do not mirror ours. But what does align is our shared commitment to collaboration and cooperation. Thankfully state and federal U.S. and Mexico law enforcement, are developing critically important working relationships.”

The power of relationship-building was especially apparent at an Alerta AMBER Regional Conference in Monterrey, Mexico, hosted by the DOJ’s Overseas Proprietorial Development Assistance and Training Section (OPDAT) in late August 2023.

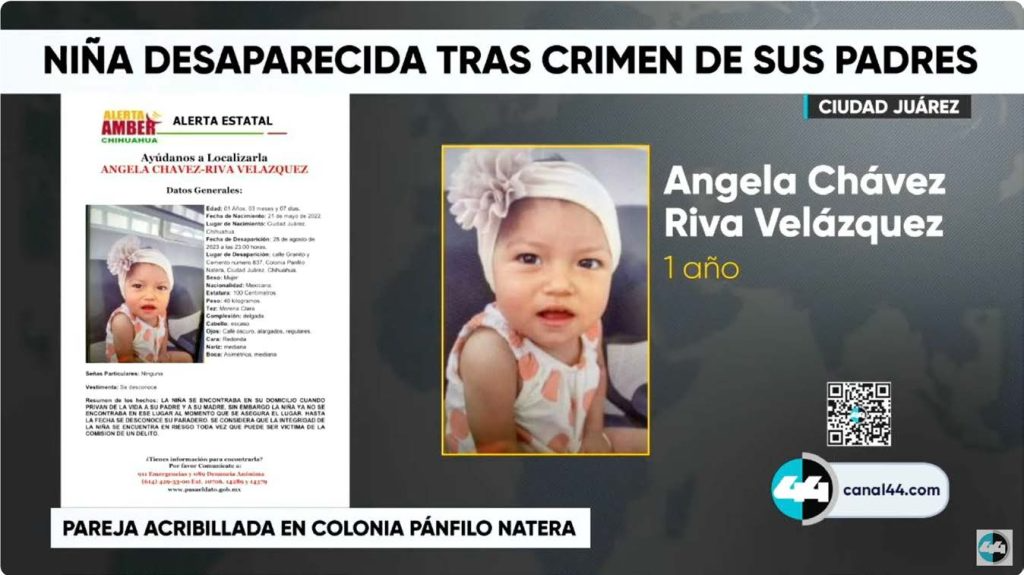

As the three-day conference began, a 1-year-old girl, Angela, was abducted August 28 after her parents were murdered during an invasion of their Ciudad Juarez home.

Yubia Yumiko Ayala Narvaez, Regional Coordinator of the Gender-Based Violence Unit/Chihuahua North Prosecutor’s Office, and Mexico’s National AMBER Alert Coordinator, Carlos Morales Rojas, were at the conference. They worked together to release national and state alerts for Angela.

Media and public response to both alerts came swiftly. (See photo above.) By the next day, the kidnappers, likely aware the case was receiving national attention, abandoned Angela in a Ciudad Juarez doorway. A woman found the infant and immediately called 911. And less than 30 hours after the issuance of the state AMBER Alert, the child was safely recovered.

“Narvaez and Rojas met for the first time as they arrived for the conference. This was just one of so many examples of how incredibly important regional events like this are to the ongoing work to build preparedness for effective response to cases of endangered missing and abducted children—in Mexico and the U.S.—through cross-border planning,” Leon-Baron says.

AATTAP’s Northern Border Initiative (NBI) also relies heavily on collaboration between Canadian provinces’ child protection officials and U.S. counterparts. Like Mexico, Canada also has Tribal components. “But the dynamics are different,” Leon-Baron explains. The professionals’ work often involves family abductions of children, either taken into or out of one country to another.

AATTAP visits have included Canadian AMBER Alert Coordinators and members of both the U.S. Customs & Border Patrol, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, and Tribal law enforcement (such as the St. Regis Mohawk Police Department). And the next NBI event—a focus group meeting—was held this September in Bonners Ferry, Idaho.

Serbia and Argentina

One of AATTAP’s highest-profile international endeavors was working with officials from the Bureau of Narcotics and International Law Enforcement (INL) and the Republic of Serbia to help that country launch its AMBER Alert-style program “Pronadji Me” (“Find Me”) in June 2023. The AATTAP-INL-New York-Virginia team also advised Bosnia-Herzegovina on their AMBER Alert-style plan.

The meeting, held at the U.S. State Department in Washington, D.C., also featured insight from Virginia and New York child protection officers. Virginia State Police AMBER Alert Coordinators Sergeant Connie Brooks and Lieutenant Robbie Goodrich outlined how their state AMBER Alert activations are decided and disseminated. Additionally, New York State Police AMBER Alert Coordinator Erika Hock, New York State Missing Persons Clearinghouse (NYSMPC) Manager Cindy Neff, and NYSMPC Investigative Supervisor Timothy Williams participated virtually to discuss their state’s AMBER Alert program requirements.

In March 2024—nine months after the U.S. meeting—Serbia activated its first “Find Me” Alert after a 2-year-old girl Dana Ilic disappeared in the town of Bor. Television and radio stations interrupted their programs to share details about Dana, including the time and place of her disappearance, and her clothes and age. Citizens also received SMS (short message service) alerts.

“Though Serbia’s first AMBER Alert sadly did not result in Dana’s safe return, the country is learning from the alert’s implementation, which will help other children who go missing,” Rasmussen says.

Although in-person meetings are always preferred, virtual meetings do have their advantages. Consider AATTAP’s one-day CART Virtual Instructor-Led Training with Argentina—an event in which AATTAP collaborated with the International Centre for Missing & Exploited Children.

“The response was overwhelming,” Leon-Baron says. “We had hundreds on our call, with many more wanting to join.” AATTAP’s next trainings with Argentina were in October.

Dominican Republic, U.S. Virgin Islands, and beyond

Meetings with child protection and government officials in the Dominican Republic and U.S. Virgin Islands have been delayed due to hurricanes, but the AATTAP planned to visit this fall.

“Our work is really just beginning,” Rasmussen says. “Now that we’ve assessed the territories’ needs, we plan to go back and help them get their AMBER Alert programs where they need to be. There is a lot of training ahead—focusing on on investigative strategies, first responders, search and rescue teams—and all of it will be informed by the geographical and cultural considerations that we have seen firsthand.”

Rebecca Sherman contributed to this report.